‘I wasn’t supposed to play the game’

13 Min Read

Reliving Lee Trevino’s unlikely road to winning the 1968 U.S. Open at Oak Hill

Lee Trevino didn’t receive much formal education—quitting school in the eighth grade to work and support his family—but by the time he showed up for the 1968 U.S. Open at Oak Hill Country Club in Rochester, New York, he effectively had a graduate degree in golf.

He was 28, a Texan seasoned by four years serving overseas in the U.S. Marines. His golf had matured by hitting more practice balls than he could count and playing in matches where the prize money came out of your opponent’s pocket.

Trevino honed his game working at Hardy’s Driving Range and its adjoining par-3 course, where he was famous for playing with a Dr. Pepper bottle. He also was a veteran of Tenison Park, the Dallas municipal course where gamblers gathered like ants at a picnic. “It is a world where a man learns to accurately take the measure of another in an instant,” sportswriter Bob Boyd wrote in 1973, “and where men trust their money and their reputations on their own abilities.”

After Dallas, Trevino moved to El Paso and a job at Horizon Hills Country Club, where he often eclipsed his $30 weekly salary as pro/locker attendant/cart man with his take in daily money games. There was a legendary multi-day match with a visiting Raymond Floyd that brought the action of a heavyweight title fight and a patchwork of onlookers.

“It was the funniest sight in the world when Raymond and I teed off,” Trevino wrote in The Snake in the Sand Trap, a 1985 memoir. “There were a bunch of pickup trucks bouncing down the fairway, full of guys drinking beer and watching our match.”

Trevino utilized his home-course advantage and savvy shotmaking to beat Floyd in their first two rounds, forcing him to shoot lights out to win on day three.

Trevino had gotten a taste of the PGA TOUR in 1962, tying for 49th in Dallas and 58th in Beaumont, failing to break par in any round. He didn’t resurface on golf’s biggest stage until 1966, when he qualified for the U.S. Open at Olympic Club. Trevino tied for 54th and won $600.

“I’d never played a great golf course like Olympic, a course with that kind of rough,” he wrote in his autobiography. “I had played municipal courses all my life and they didn’t have rough. Or bunkers.

“I decided if that was what the U.S. Open was like, I wasn’t going to mess with it too much.”

His struggles at Olympic, and lack of money, left him with little interest in returning to his national championship. But his wife scraped together the $20 entry fee in 1967 and he again made it through qualifying.

It was his appearance in the 1967 U.S. Open at Baltusrol Golf Club in New Jersey—Jack Nicklaus outdueled Arnold Palmer—that helped Trevino really establish himself. He arrived with $50 in his pocket but finished fifth after rounds of 72-70-71-70. He earned $6,000 and credited his wife for “shoving me” out onto the TOUR. He only missed one cut the rest of the season and had two more top-10s, finishing 45th on the money list with $26,473 and securing an exemption for 1968 as one of the top 60 money earners.

Trevino didn’t skip a beat once the new season began, tying for eighth in Los Angeles and sixth in Palm Springs. He heated up in the spring with runner-up finishes in Houston and Atlanta and a tie for fourth in Fort Worth. But for Trevino to complete his improbable climb from obscurity to the game’s top rung he needed to win.

“I wasn't supposed to play this game. But for some reason, and I've made this statement many times, it wasn't hard for me.”

Lee Trevino

He did it in high style, bettering rugged Oak Hill’s par of 70 each day at the ’68 U.S. Open, a first for the national championship. In the final round, which he began a stroke behind Bert Yancey, Trevino shot 69 alongside the leader, whose putter betrayed him in a closing 76. Nicklaus’ 67 zoomed him up the leaderboard but only into second place, four shots behind Trevino.

“It’s all like a dream,” Trevino said. He made birdie putts of 35 and 20 feet at Nos. 11 and 12, respectively, hit the flagstick with his tee shot on the par-3 15th and saved par on the final hole with a wedge shot after his attempt to extract his ball from the rough with a 6-iron didn’t escape the tall stuff. He knocked his third shot to 4 feet and made the putt to shoot 69.

Trevino’s scoring—he tied Nicklaus’ record 275 total for 72 holes set at Baltusrol—wasn’t the only thing in the red. So were Trevino’s shirt, socks and glove on Sunday. But with the chattering and the ball-striking he would have stood out in head-to-toe beige, an American original atop American golf.

Below is a Q&A with the World Golf Hall of Famer from last month’s Insperity Invitational. The conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity. Trevino discusses why he wasn’t supposed to play golf, his unlikely upbringing and the special putter a friend made for him to use at Oak Hill.

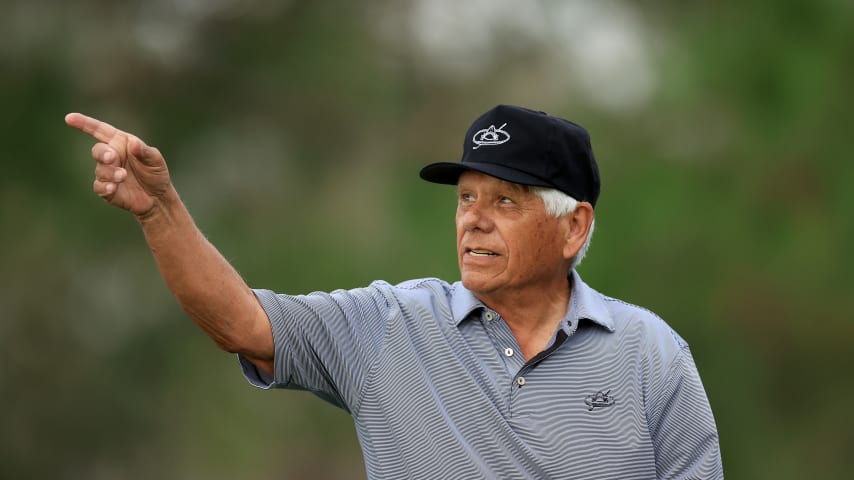

Lee Trevino at the 2022 PNC Championship in Orlando, Florida. (David Cannon/Getty Images)

PGATOUR.COM: What made you fall in love with the game of golf and that it has lasted as many decades as it has?

LEE TREVINO: Well, first of all, I fell into this. I didn't have a love of golf. In other words, I really didn't start playing golf until I was 22 years old. I got in a little bit of trouble when I was 16, almost 17 years old, and I ended up going in the Marine Corps, and I spent four years in the Marine Corps. When I got out, I still didn't pursue it. I had caddied a little bit. I had been around golf as a youngster. But I didn't play. I hit a few balls here and there, whatever. I enjoyed doing it when I did it, but I didn't think I had any future in it.

I knew that back when I played golf in the early '50s and stuff that it was a wealthy man's game. When I got out of the Marine Corps, I went to work at the Columbian Club building a new nine holes. I was actually welding the irrigation system, and I'd practice and play a little bit, and then the next thing you know, I started getting better and better and better and started beating everyone.

Probably the smartest thing I ever did was I went to work for Hardy, who had a driving range there in Dallas, and I went to work at a driving range on a par-3 course and I started practicing and I started getting better and better and better and I practiced four years. I entered my first tournament in Houston, Sharpstown, the Texas State Open, and I won it in a playoff, won the New Mexico Open a month and a half later, and qualified for the Open in '66, '67, and won the Open in '68.

I wasn't supposed to play this game. But for some reason, and I've made this statement many times, it wasn't hard for me. I don't know why. I have no clue. Unorthodox swing, I didn't swing like everybody else. But this game is about numbers. The lower the number, the better. That's what I was good at.

Q. What is your favorite story from Oak Hill in '68?

LEE TREVINO: Well, I stayed with a family there that was fantastic. The Kircher family. I always made it a point to never stay at any people's houses because I did that in Memphis one time, a gentleman asked me to come and have dinner with him and he had 200 people in the backyard there when I got there.

That didn't go over very well, but I learned a lesson. The important lesson was when you go to a golf tournament, go to a golf tournament to play a golf tournament and on your own time.

They kept writing me letters. Paul Kircher, and he had like seven kids, and they kept writing me letters and sending me pictures about staying at their house. They lived on Arlington Street, right next to Monroe, the other golf course there, and for some reason I accepted it.

The youngest daughter, which is Susan, is a big-time lawyer now there in Rochester. She was 2 years old when I went there. We used to go out in the backyard and lay on the grass and look for four-leaf clovers, and we found one, and I stuck it in my back pocket and carried it the whole week.

The other thing that reminds me about Oak Hill is Dennis Lavender, who was the old golf pro at Cedar Crest, where Walter Hagen won the 1927 PGA.

Dennis and I used to play nine holes about three times a week. He told me that when I qualified to go up there, “You're going up to a golf course that has different greens than you're used to putting on. You're putting on Bermuda here, you're going up there to putt on bent. It's a different grass; it's faster.” He said, “I'm going to go in the back and build you a putter.” He went in the back, and he built me a Tommy Armour reverse A 3852. Iron Master it was called. That's the putter that I won the tournament with. I still have it.

Q. You made some really good putts on 11 and 12 coming down the stretch there. Were there any nerves?

LEE TREVINO: No. No, I had played pretty well going into that golf tournament. I remember playing four practice rounds with Doug Sanders, and Doug Sanders says, “I'm going to go make a bet on you.” He said, “You didn't miss a fairway the four days we played.” I said, “Well, I don't miss many fairways. I aim down the left and the ball goes right.” Nicklaus did the same thing but Nicklaus hit it 60 yards longer than I did. I drove the ball well.

If there was any nerves at all it was on the first hole on the last day when Bert Yancey and I teed off. I remember I bogeyed the first hole, and I didn't make it to the fairway on the left. I was going to hit a cut and I heeled it and it went low and it didn't make the fairway. It stayed in the rough, and I ended up making bogey on the first hole.

Then the nerves settled.

I was having some nerves coming down the stretch because if you look back at that reel, I realized that I was five shots ahead when I stood on the 16th tee.

I had a guy by the name of Kevin Quinn as my caddie, a young man, who was in college or a senior in high school. Great feeling standing on the 18th tee with that big of a lead. So I looked at him, and I said, “Is there any out of bounds here?” He said no. So I aimed it down the left side, and I was going to kill one, and I pulled it in the rough.

My ball is in the rough, in the tall rough, and he's looking at the ball, and I'm looking at the ball. He says, “Listen, take a wedge out and just put it in the front, put it on the green.” I didn't realize that if I parred the 18th hole, I'd be the first man to shoot four rounds in the 60s in a U.S. Open.

I stood there, and I said, “No, I don't want to be remembered as the guy that wins the U.S. Open laying up.” I said, “I don't lay up. Give me the 6-iron.” I laid the grass right over it, and it went about 50 yards, and I was still in the rough.

So then I walked up and I took the wedge and I put it about 4 feet to the right of the hole, and I holed it for a 4. I ended up shooting four rounds in the 60s, the first guy to ever do it. I did not know that that record was there.

Q. The 1967 U.S. Open at Baltusrol, how significant was that for you knowing in you belonged out here?

LEE TREVINO: I never thought that. I never thought I belonged out here until 1971 when I beat Jack in a playoff in the U.S. Open at Merion. When I won that and I shot 68 and I think Jack shot 71 if I'm not mistaken, that was the first time that actually the golf pros that really didn't speak to me much came up and embraced me and said, man, you did great. I'm glad we've got somebody out here that can beat this guy. They were telling me all this stuff. It was the next week in Cleveland at Aurora when they did this. When I walked away from there, I felt like, yeah, I'm part of the guys now. I'm part of the gang.

Q. You were known for having a unique swing and being one of the game’s great ballstrikers. What was the secret to your success?

LEE TREVINO: The big thing about it is when I was in the Marine Corps and I was hitting some balls, I had a duck hook. I swung like everybody else. I was more upright, my grip was a little stronger. I worked the ball from right to left. I never knew that you could work the ball from left to right. I didn't think anybody wanted to do that because what is the first thing that people talk about? A slice. They never talk about a draw. They always say, oh, I'm slicing it. It's like poison. No, it's not. The ball working from left to right is actually -- it's actually gold. If you know how to work it.

I did it because I was watching Mr. Hogan practice, and I could see his ball working left to right. Now, we had the balata ball, it was easier to work. The problem is that you can't hit the ball very far when you fade it, simply because you have to hold. There's no release. You're not releasing the club.

So I went back home and started trying to figure out how in the world to hit the ball and make it go to the right. So I figured out if I held it and didn't rotate that the ball would curve to the right, and that's how I learned to play. That's why it went lower, and that's why it faded a little bit.

Fortunately we played a lot of Donald Ross golf courses and shorter courses. I would have had to adapt if I came along today. I wouldn't have been able to play that way.

Q. At what point where you ever comfortable with your position in the game of golf?

LEE TREVINO: You know, the funny thing about me is that you can't embarrass me. I never feel uncomfortable anyplace. The reason for it is because the good Lord bestowed a talent on me, and I took advantage of it. I work just as hard at this game today as I did when I was 30 years old, and the reason for it is because I'm going to have to meet him some day, and I don't want him to be disappointed. I didn't have much help except for the man upstairs along the way.

I'm pretty proud of that.

Doug Milne contributed to the creation of this article