A look back at Payne Stewart's three majors

7 Min Read

Written by Cameron Morfit

Payne Stewart played the harmonica and traveled with novelty teeth. He loved a fight – with a nasty golf course, especially – and was famous for his liquid-smoke barbecue sauce. He ironed his own clothes, and yet wasn’t afraid to pose for a Golf Digest cover with a chimpanzee on his back.

And he was a battler, distilling lessons from his hard-knock losses to build his golfing legacy.

On the 30-year anniversary of his first major win, the 1989 PGA Championship at Kemper Lakes, and the 20-year anniversary of his third and last, the 1999 U.S. Open at Pinehurst No. 2, the feisty Stewart’s toughness in the big moments is the common theme.

He finished strong.

THE PAYNE STEWART AWARD is presented annually by the PGA TOUR to a professional golfer who best exemplifies Stewart’s steadfast values of character, charity and sportsmanship.For more coverage, click here.

All those losses? They helped steel him to finally get the monkey (or chimp) off his back. He learned how to manage his ADD and proved that while he sometimes struggled to concentrate, he also could summon a furious focus when locked in.

His final bravura performance? Well, that was partly fate, too. Because four months after Stewart edged Phil Mickelson by one at misty Pinehurst, he boarded a Learjet in his hometown of Orlando, bound for the season-ending TOUR Championship in Texas, and was killed along with five other passengers when the plane depressurized before crashing in a field in South Dakota.

“To lose Payne so soon after Pinehurst, it gave that tournament a kind of mythical quality,” Peter Jacobsen told Golf Magazine for a lengthy oral history years later.

Yes, it did.

Here’s a look back at Stewart’s three career-defining victories:

1989 PGA Championship

Stewart would compile 11 PGA TOUR victories, including three majors, and be posthumously inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame. He was very, very good.

This week, though, he was both good and lucky.

“Man, this is unbelievable,” he said afterward.

So it was for the loser, was well. Mike Reid, whose “Radar” nickname was a nod to his accuracy, was so shattered he had to stop several times to compose himself.

Indeed, it was the type of tournament you had to watch through your fingers. Reid, a slender and bespectacled Utahan who had led but failed to close on the back nine at the Masters just four months earlier, was going to atone for that at Kemper Lakes outside Chicago.

He led after every round. He led by three shots with three holes to play. And then he lost.

Reid blocked his drive into the water at the 469-yard, par-4 16th, and faced a 12-footer just to save bogey. He made it, but then came unglued. After his 4-iron tee shot went long on 17, Reid fluffed his chip shot, leaving his ball some 15 feet short. He three-putted for double-bogey.

Stewart had birdied four of the last five holes, which meant that Reid was now one behind. He parked his approach shot to just seven feet from the pin on 18. He wasn’t dead yet! He missed.

“I guess the Russians must have been transmitting,” a somber Reid said afterward as he gamely answered reporters’ questions, “because my radar just got zapped.”

Stewart, meanwhile, was resilient. He began the final day six shots behind, with 10 players ahead of him. Dressed in the colors of the Chicago Bears, he went out in even-par 36, but told ABC on-course commentator Jerry Pate he thought he might shoot 31 on the back nine.

He did.

1991 U.S. Open

A storm punished Hazeltine in the first round, and after the horn blew, lightning struck a group of spectators as they stood under a tree next to the 11th tee. One of them had a heart attack and was revived, but later died in the hospital. He was only 27.

As a result, Stewart was somber even after shooting an opening-round 67 to tie Nolan Henke.

“I’m excited about the way I played,” he said. “I didn’t really have any expectations.”

Indeed, Stewart had only one top-10 finish in 12 starts going into the U.S. Open. Some of that was due to injury; he sat out March and much of April with a sprained neck.

His main competition would not be Henke but the soft-spoken, mustachioed 1987 U.S. Open champion Simpson. All he’d done since winning at Olympic Club was finish sixth, sixth, and 14th in the three subsequent U.S. Opens. It seemed he was becoming a specialist.

He’d have added another trophy to his collection had he figured out the last three holes.

Up two with three to play in the final round of regulation play Sunday, Simpson bogeyed 16 and 18 to fall back into a tie with Stewart. Both signed for 72, met the press, and went for dinner before tucking into bed to rest up for an 18-hole Monday playoff.

The next day, history repeated itself. Again, Simpson took a two-shot lead into 16, only to bogey the hole as his three-foot par try lipped out. Perhaps he was rattled; Stewart had just birdied from 20 feet, his first birdie after going 30 holes without one, and now they were tied.

When Simpson bogeyed 17 and 18, too, Stewart was the winner by two, 75 to 77.

“It’s disappointing to lose the U.S. Open two days in a row,” Simpson said.

Admittedly fortunate, Stewart said of his second 11th-hour comeback in as many days, “It was the same song, second verse. It was a grind all day. I didn’t quit, and it showed me if I ever quit, I’m an idiot, because a lot of funny things can happen on the way to the clubhouse.”

The oddest of these, other than Simpson’s repeat swoon on the final three holes, happened at the par-3 eighth hole in the Monday playoff. Stewart’s tee shot was headed for the lake, wide right, but his ball hit a partially submerged rock and ricocheted back on dry land.

It was his week.

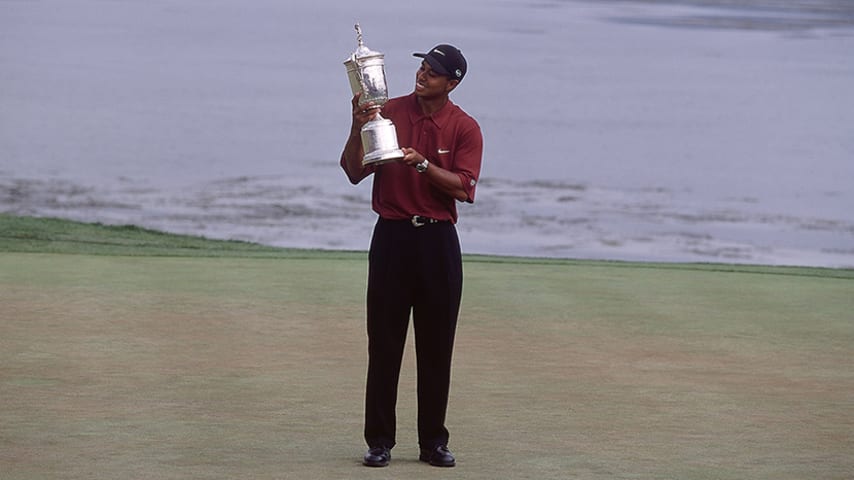

1999 U.S. Open

Stewart busted out a pair of scissors and sheered the sleeves off his dark-blue rain jacket. When the rain abated, leaving an ethereal mist hanging over Pinehurst, the actors took their places for what has been called the “Beeper Open” and the greatest U.S. Open ever.

It wasn’t just Stewart and Mickelson but also Tiger Woods, David Duval and Vijay Singh in the mix to win the first U.S. Open at Pinehurst No. 2. There was a redemption narrative in play, as well, as just the year before, at the 1998 U.S. Open at Olympic Club, Stewart had taken a fat four-shot lead into the final round only to shoot 74 to lose to Lee Janzen (68).

Most of all, though, Pinehurst in ’99 was about the wives.

Amy Mickelson was very pregnant and back home in Scottsdale, Arizona. She and Phil set up Jim “Bones” Mackay, then Mickelson’s caddie, to carry a beeper. There were complications, but she kept these mostly to herself so Mickelson could focus on trying to win his first major.

In the other camp, Stewart birdied 18 to take a one-shot lead with one round remaining, but his wife, Tracey, had seen something: His head was moving on putts. Stewart, who had overdone it with the media on the Saturday of the ’98 U.S. Open, running out of daylight in which to practice after the third round, didn’t make the same mistake twice. Heeding Tracey’s message, he went to the practice green to work on his stroke until darkness, careful to keep his head still.

The next day, Father’s Day, he woke up, ironed his clothes and cried as he watched an NBC segment about himself and his late father, the great Missouri amateur Bill Stewart.

On the course, though, he was all business. He made a 30-foot par save on 16; a four-foot birdie on 17 (Mickelson missed from six feet); and a 15-foot par putt on 18 to close it out by one. He punched the air, all of his weight on his front leg, and later cupped Mickelson’s cheeks. “Good luck with the baby!” he said. “There’s nothing like being a father!”

Stewart hugged Tracey and they cried tears of joy. Years later, she would revealwhat he said:

“Lovey, I didn’t move my head all day on those putts, just like you said. I didn’t move it once.”