Inside the renovation that couldn’t fail at Colonial Country Club

13 Min Read

Sneak preview of Colonial Country Club golf course renovation

Written by Paul Hodowanic

FORT WORTH, Texas – It was a late-June morning and the sun was well below the horizon when Rich McIntosh, Oscar Lazaro and Josh McFadden piled into a small, dimly lit trailer at the center of Colonial Country Club.

The men sat around a plastic folding table, analyzing a large map of the course and planning the day ahead. Filled with markings and highlights, the map showed tangible progress that was hard to grasp when looking at the setting that surrounded them. The historic Colonial Country Club, where Ben Hogan once ruled, barely looked like a golf course. Every blade of grass on the back nine was gone. Only giant mounds of dirt remained. The front nine would soon look the same.

Lazaro, the lead man for LaBar Golf Renovations, discussed plans to fortify drain lines near the 15th tee and 17th green. McFadden, one of the shapers, had work to do on the 12th fairway, adjusting sightlines that would affect the tee shot. McIntosh, Colonial’s director of agronomy and project manager for the renovation, directed traffic. Other crews were ready to laser-scan the front nine greens and prep for the demo.

“Another busy day,” Lazaro said.

There would be many more like it. Still 10 months from their deadline, a quiet intensity loomed over every decision and action. Crews began ripping up Colonial less than 24 hours after Emiliano Grillo beat Adam Schenk in a playoff to claim the 2023 Charles Schwab Challenge, and they did so with an ambitious directive: fully renovate one of the most historic courses in America in time for the PGA TOUR’s annual visit the following May.

A project of such scale normally takes at least 18 months to complete; Colonial had little less than a year, though. As the venue for the Charles Schwab Challenge since 1946, Colonial hosts the longest-running TOUR event held annually at the same site. The club had no intention of interrupting that streak. The renovation had to fit its schedule.

Gil Hanse, the renowned architect in charge of restoring the 1936 Perry Maxwell design, had worked under similar time constraints only a handful of times before. Each of those had more favorable growing seasons. Colonial’s renovation banked on the course surviving the winter.

Hanse, McIntosh and their teams had spent the last year with those stakes as their backdrop. The $20 million renovation, designed to reinvigorate the classic design and maintain Colonial’s reputation as one of the top clubs in the country, was accompanied by an unforgiving timeline. The world would know if the course wasn’t ready, and there would be no time for adjustments. The pros playing Colonial this week are the first to play the course. Members won’t play it for another month.

“When you have a deadline like this, you really can’t fail,” Hanse said. “There’s so much riding on it.”

For weeks, Colonial's fairways looked like thoroughfares in Texas’ scorching, late-summer sun.

McIntosh set an Oct. 1 deadline to re-sod the entire course. That would give the roots enough time to catch the underlying soil before winter hit. The grass wouldn't survive the cold conditions if given too short of a growing window. But installation doesn’t just happen over a few days. Crews laid down 118 acres of grass, the equivalent of more than 89 football fields. It took somewhere between 600-650 trucks to carry in every piece of sod, McIntosh said, and crews could only install about 10 trucks worth of sod a day.

Simple math meant they needed to budget about two months for turf installation, which meant any work to the underlying ground – irrigation, new hydronic systems in the greens or significant changes to the terrain – had to be completed in the three months prior.

From June to October, the project could hardly afford any hiccups. If one critical piece of the puzzle was delayed, it could throw off the whole plan. The margin for error was slim. McIntosh had previously worked on renovations at Torrey Pines and Muirfield Village, but those were nothing compared to Colonial.

“It's one of the biggest and tightest timeline projects anywhere,” he said. “I haven't been a part of something where we've completely redone everything and moved the amount of dirt that we have.”

It was an unnerving proposition for every party, including the membership. Longtime Colonial member Ryan Palmer, who’s won four times in 21 seasons on the PGA TOUR, was entrenched in the renovation talks from the beginning.

“It was shocking, to be honest with you,” Palmer said of the proposed timeline.

“We couldn’t miss,” McIntosh said.

That was clear in more ways than one. In 2008, Keith Foster partially renovated Colonial, but the membership quickly realized it didn’t go far enough in restoring the course to its original Perry Maxwell design. Within eight years, the club was mulling its options, uninterested in half-measures. They needed to do it right this time, and could ill afford to go back to the drawing board again. This renovation needed to set them up for decades.

That led Colonial to Hanse, who they believed could meet their standards. And schedule.

A mutual friend connected club executives with Hanse in 2016, when he was re-doing the Black Course at the Streamsong Resort in central Florida. Colonial’s membership took some convincing, though. Especially Palmer, who infamously spent an entire evening grilling Hanse on his previous renovation work, hoping to get some clarity about the architect’s design philosophy and his plans for Colonial.

Hanse’s vision eventually won over the members, including the PGA TOUR winner in their midst, but figuring out when the renovation would happen took much longer than expected. The COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing supply chain issues, which would have jeopardized the short timeline, delayed the project.

Waiting proved wise, as the project went through without any snafus.

The greens were finished by Sept. 1, 2023, and the final piece of sod was planted in the first week of November. They hit every mark, yet they still weren’t in the clear.

The weather was the last hurdle. The renovation team did everything right, but the course was susceptible if the Dallas-Fort Worth area had a harsh winter. An extended freeze could thwart all the growing progress that was made in the fall. McIntosh was alarmed by a five-day freeze in January that left the entire course dormant, but the winter remained mostly mild from there. Three weeks before the Charles Schwab Challenge, the greens looked “immaculate,” he said, with only a few patchy fairway areas left to clean up.

“I'd be lying if I said I was 100% confident we'd be standing here three weeks from now getting ready for a golf tournament on a perfectly presented golf course,” Hanse said. “The vast majority of the space is ready to go.”

Hanse was always the man for the job.

Before being hired by Colonial, he’d established himself as the go-to architect for prestigious clubs seeking to breathe life into aging layouts and bring them back to their golden age. Several of the top courses in the country had already entrusted Hanse to rejuvenate their courses and restore the vision of the original architect. Hanse was known for not forcing a new philosophy onto these historic grounds; instead, he mined the club’s history to uncover what made the course great, then worked to bring that vision back to life while making it fit into the modern game.

Hanse has restored three of the last four U.S. Open host sites – The Los Angeles Country Club, The Country Club in Brookline (Massachusetts) and Winged Foot Golf Club in Mamaroneck, New York – along with the 2022 PGA Championship venue, Southern Hills Country Club in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Hanse’s resume also includes restorations at Oakmont, Merion, The Olympic Club and Baltusrol, all of which are slated to host upcoming majors.

Hanse and business partner Jim Wagner are best known for their vast Rolodex of restoration and renovation projects, though they do have several notable original designs, including Fields Ranch East at the PGA of America’s headquarters in Frisco, Texas, the Olympic Golf Course used in the 2016 Rio De Janeiro Games, Scotland’s Castle Stuart Golf Links, Pinehurst No. 4, Boston Golf Club and Rustic Canyon Golf Course in California.

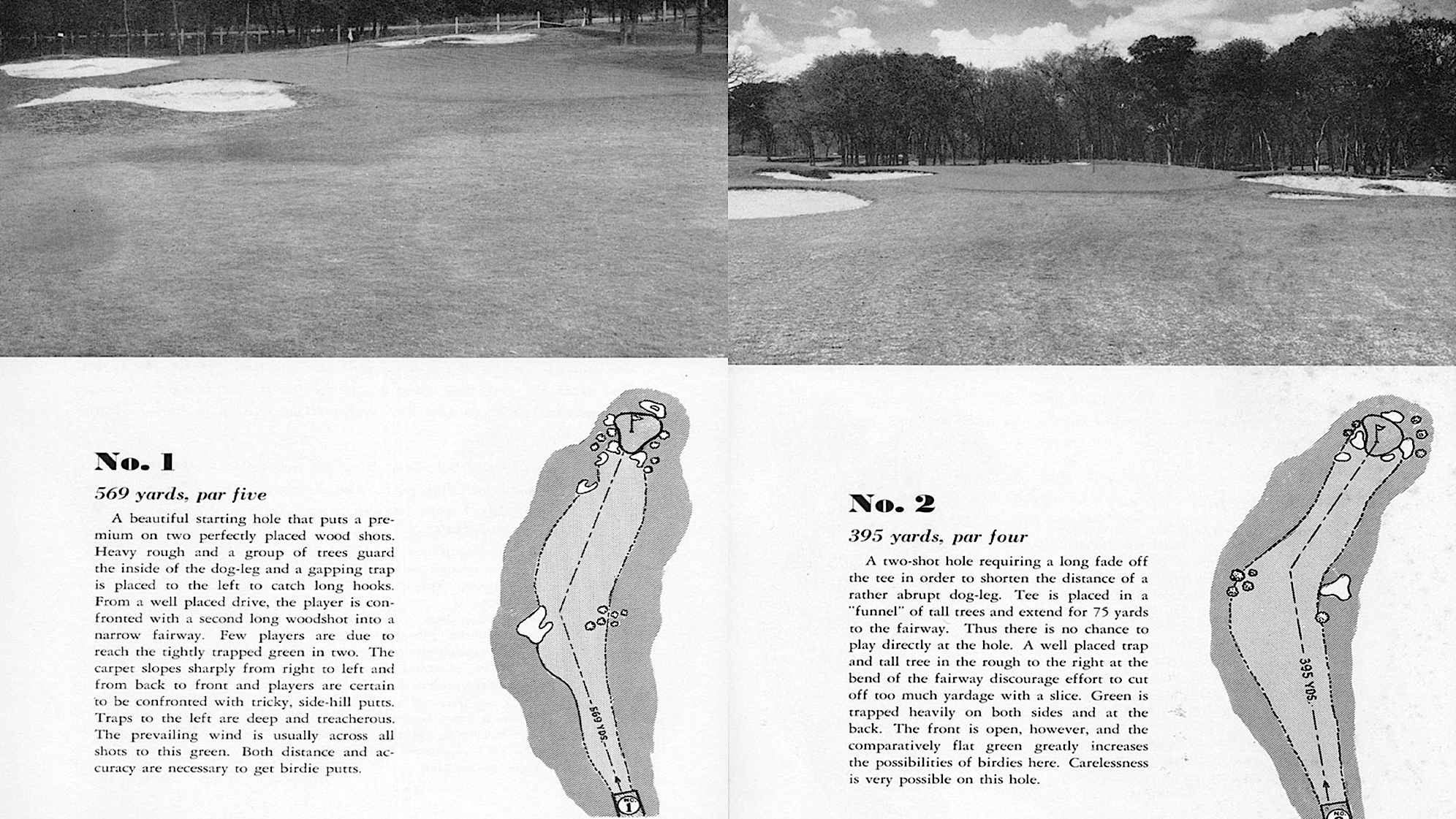

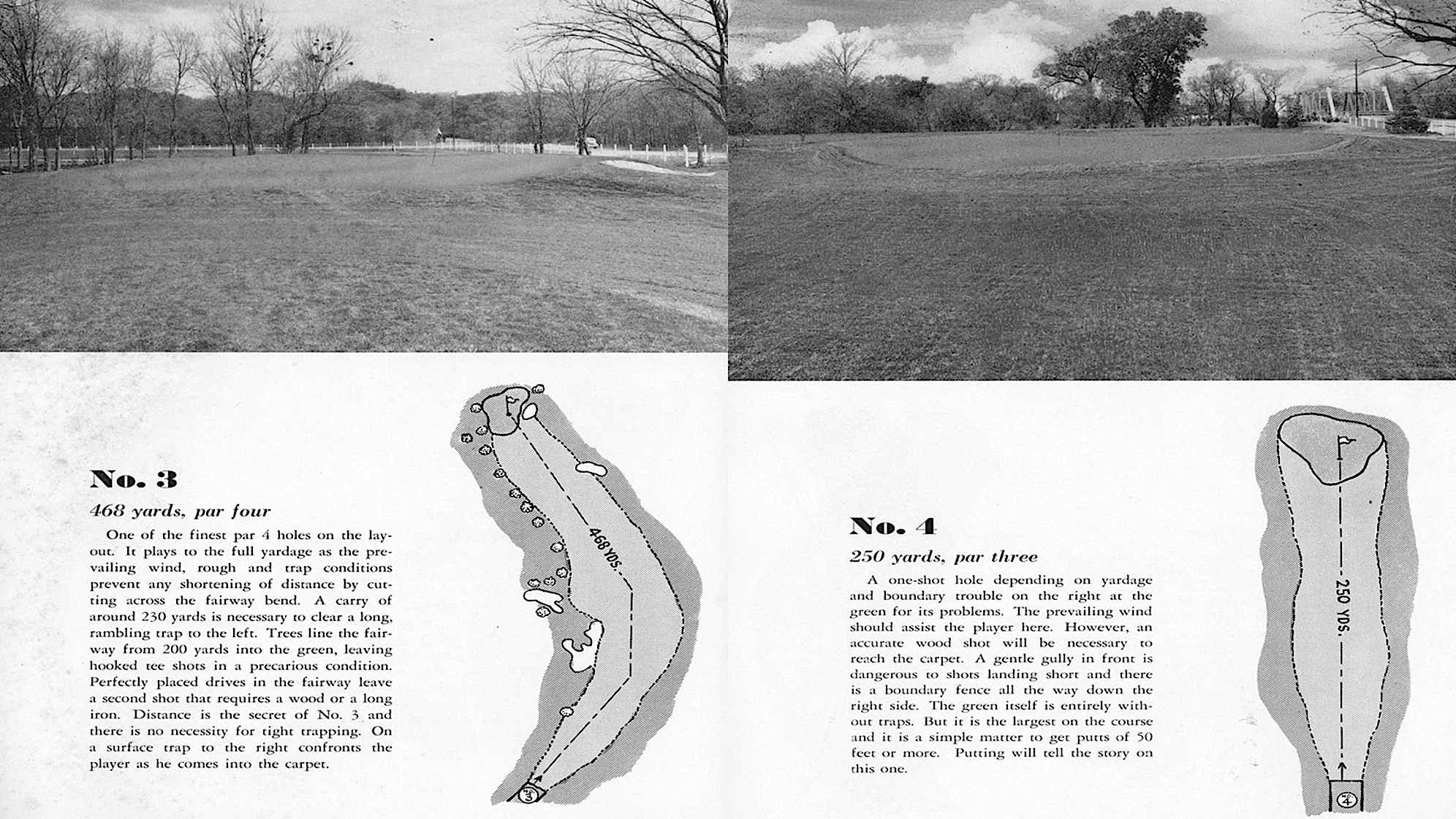

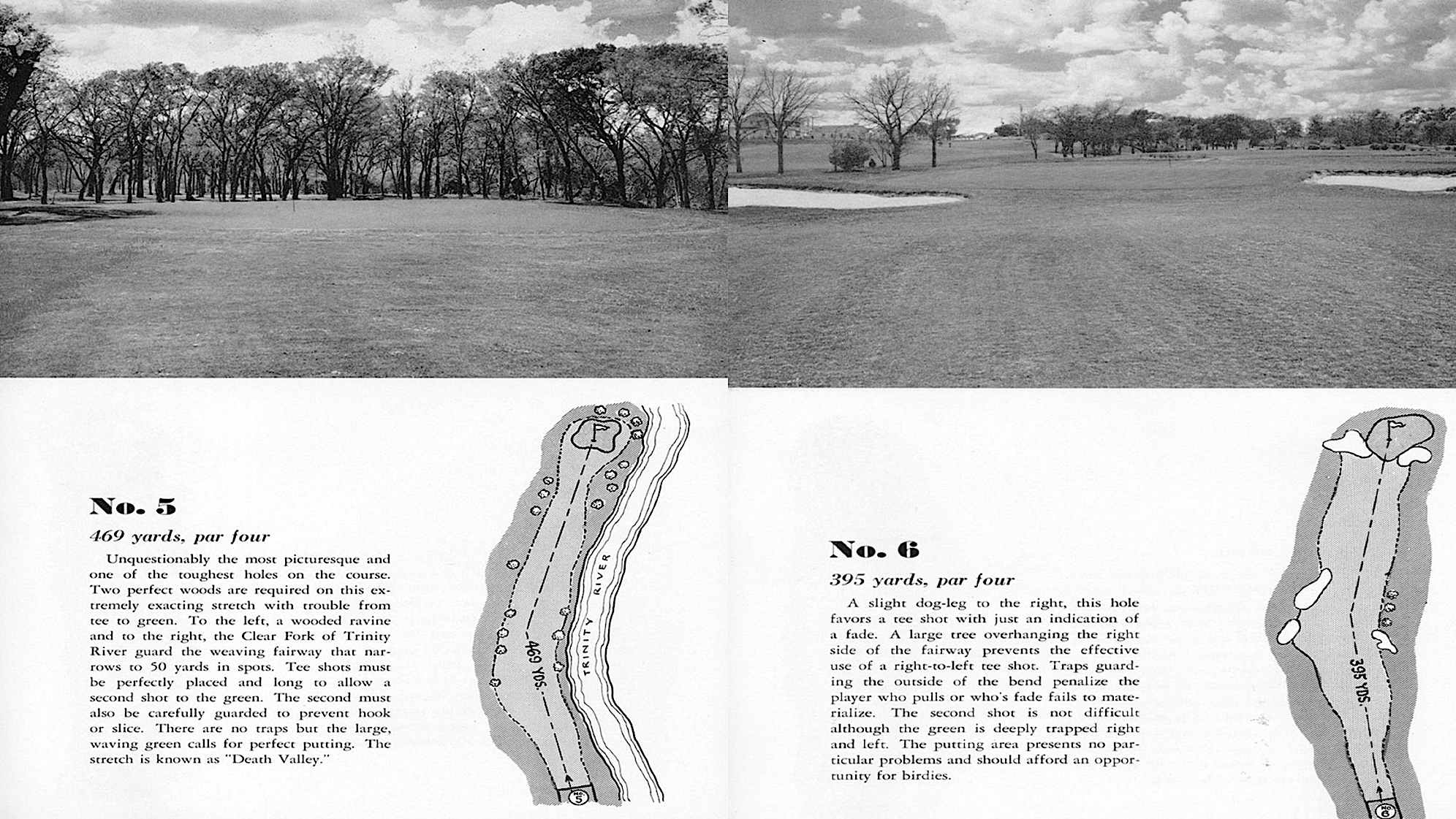

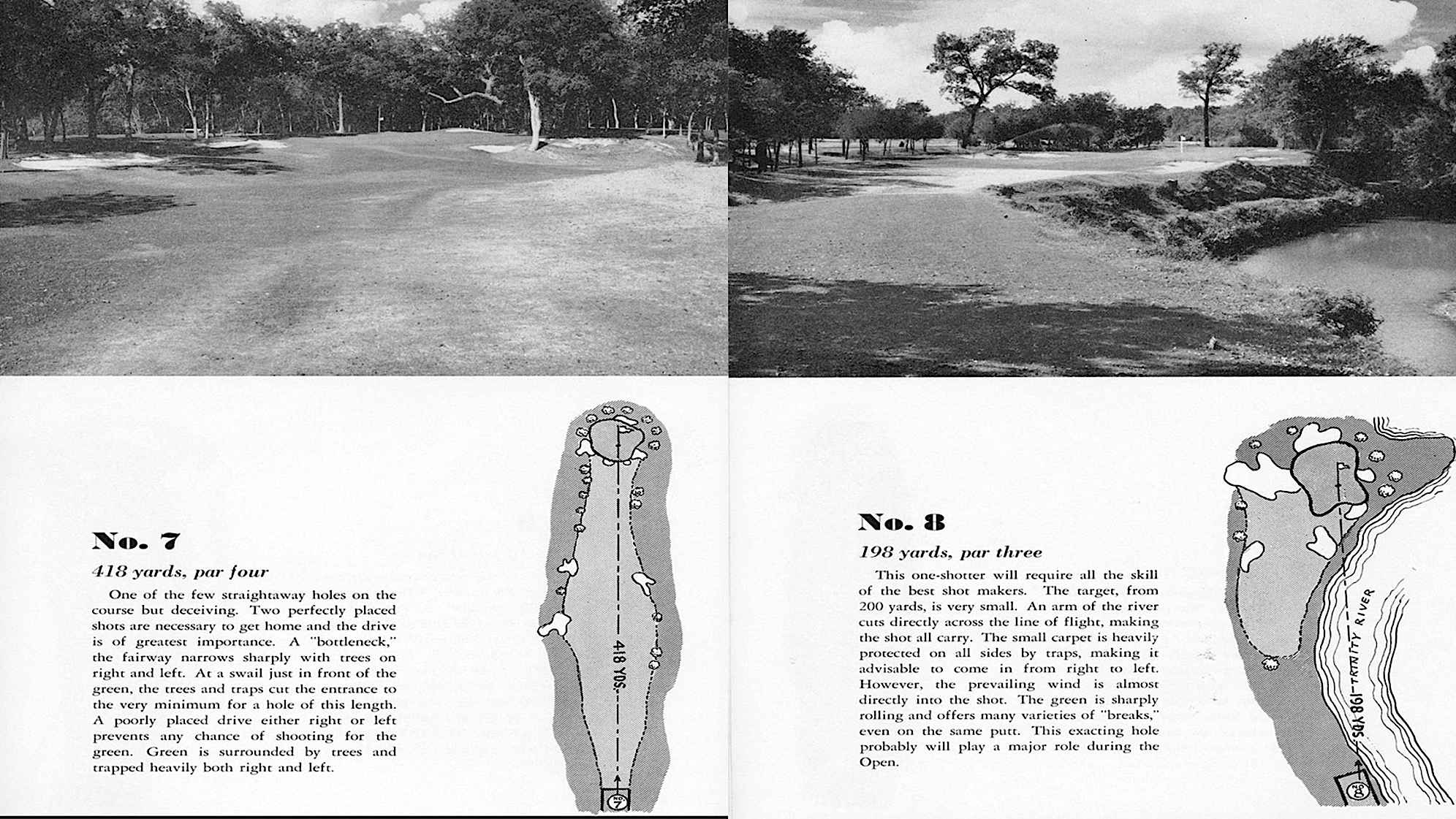

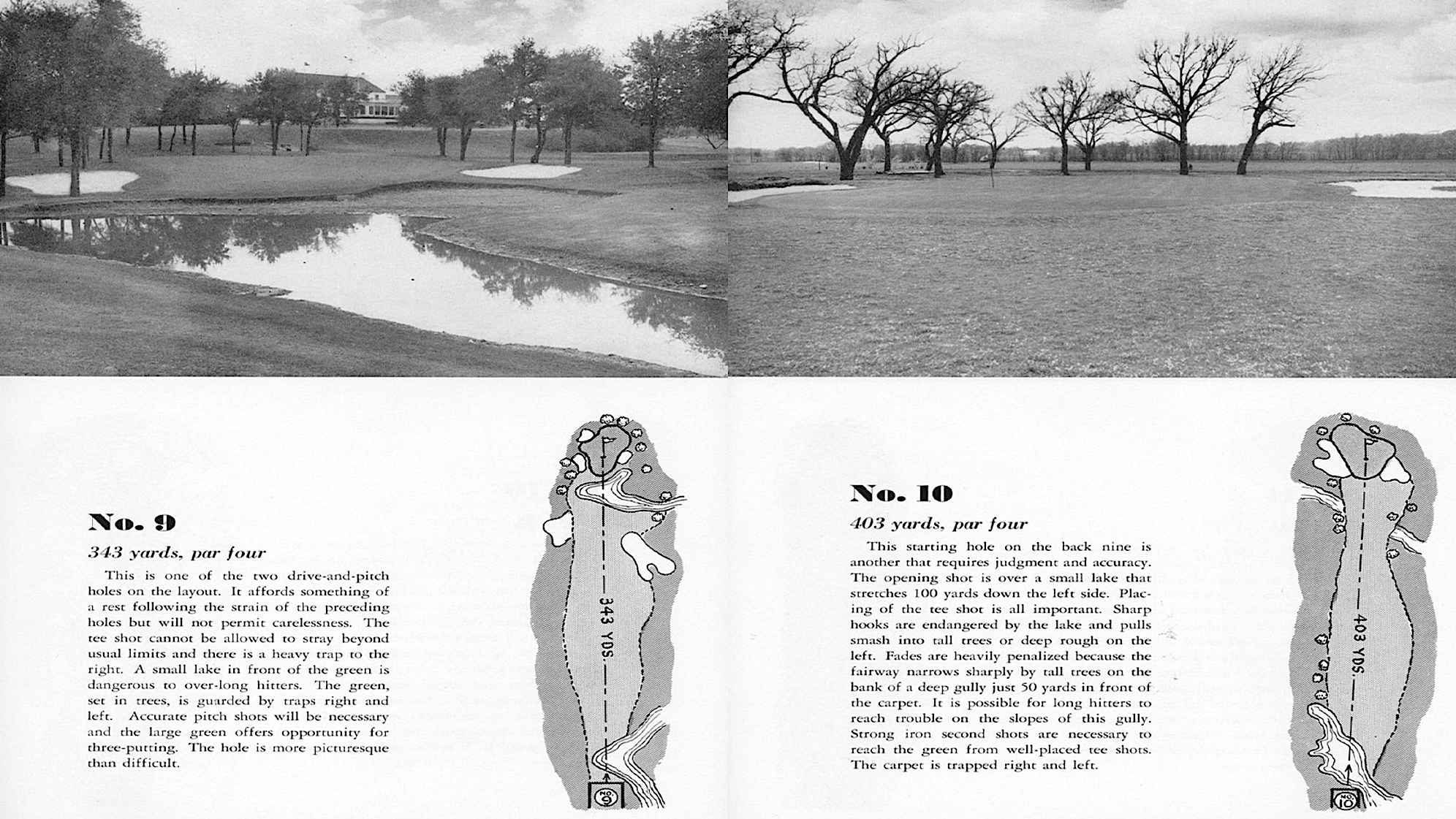

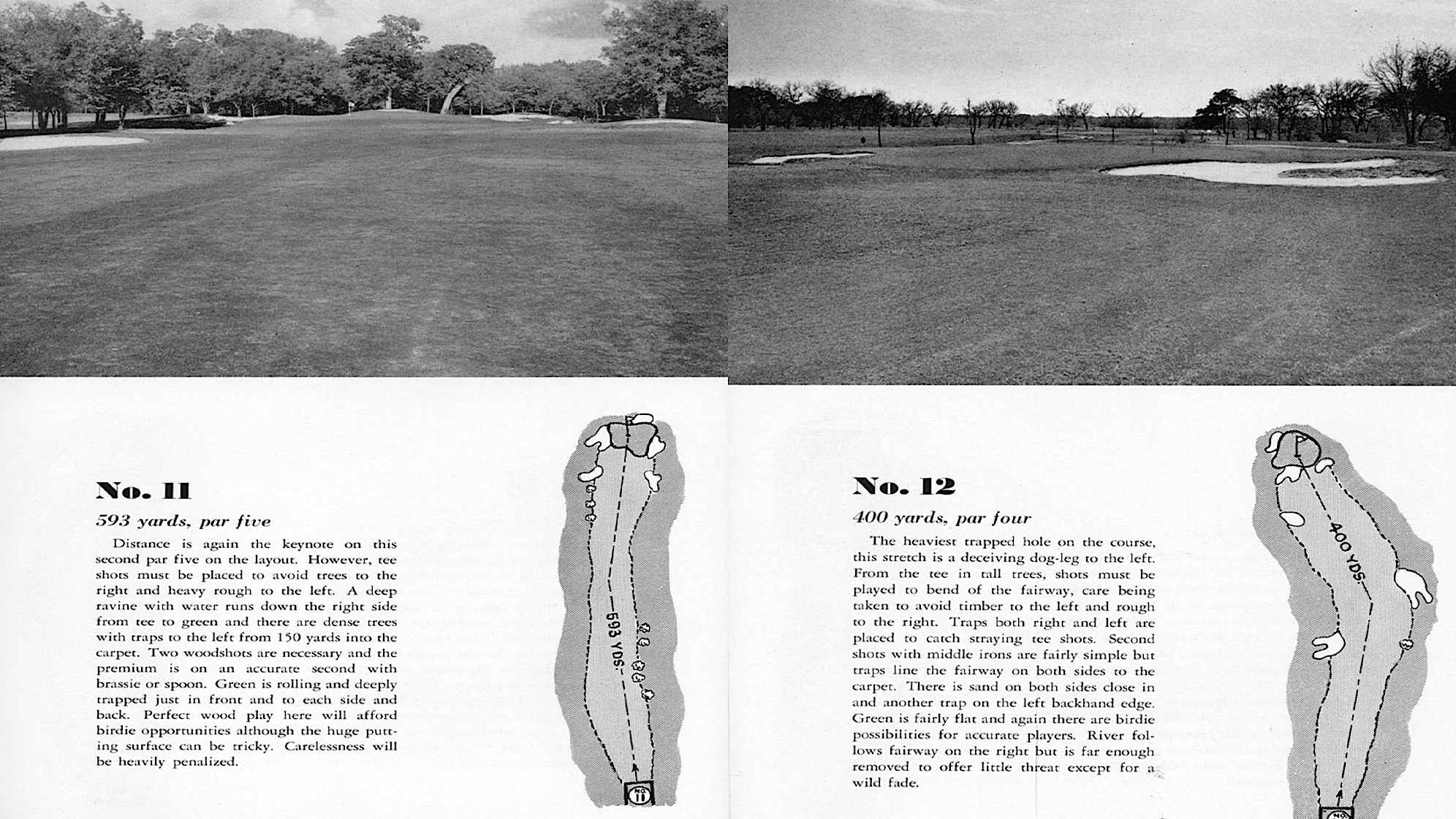

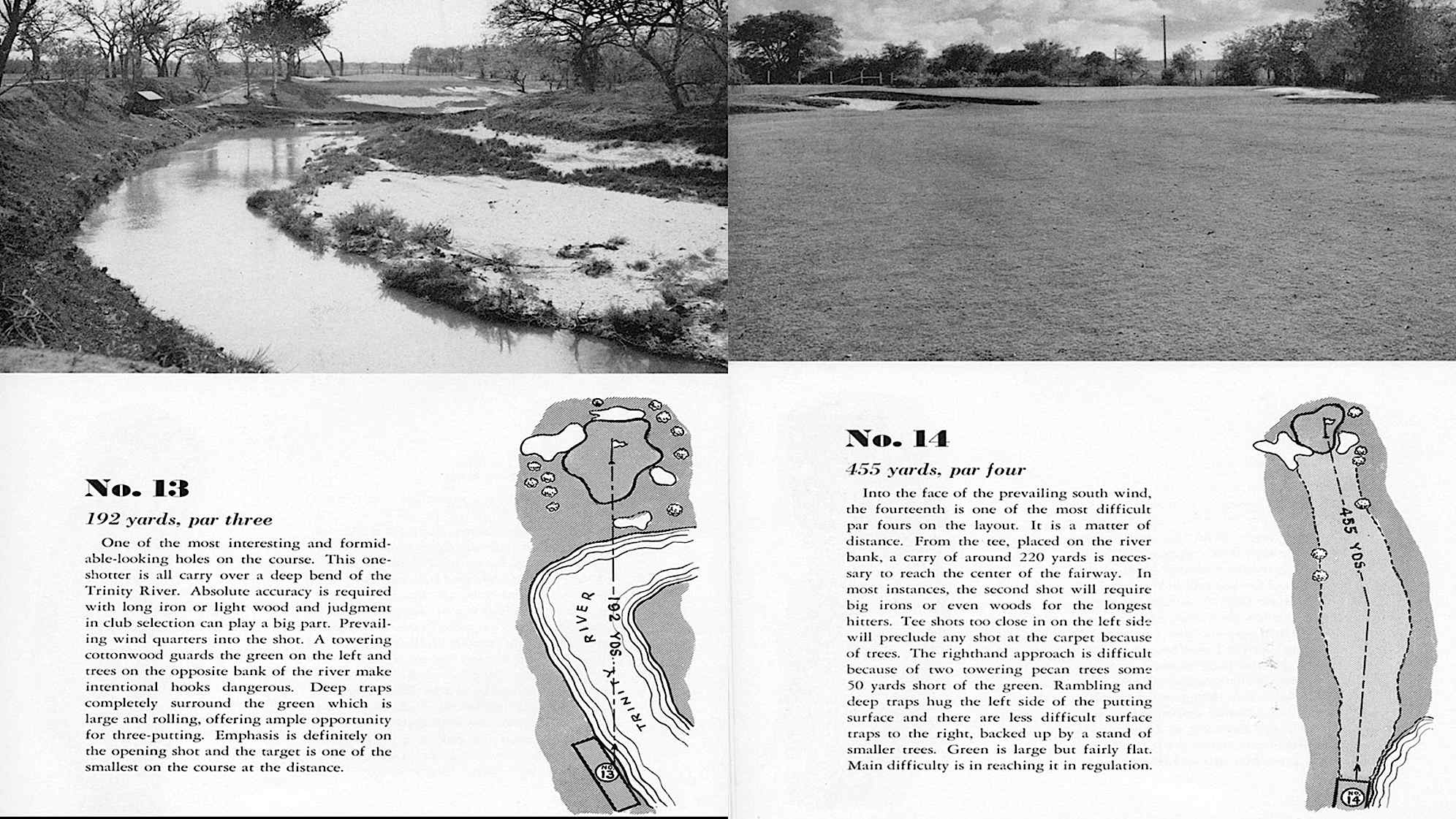

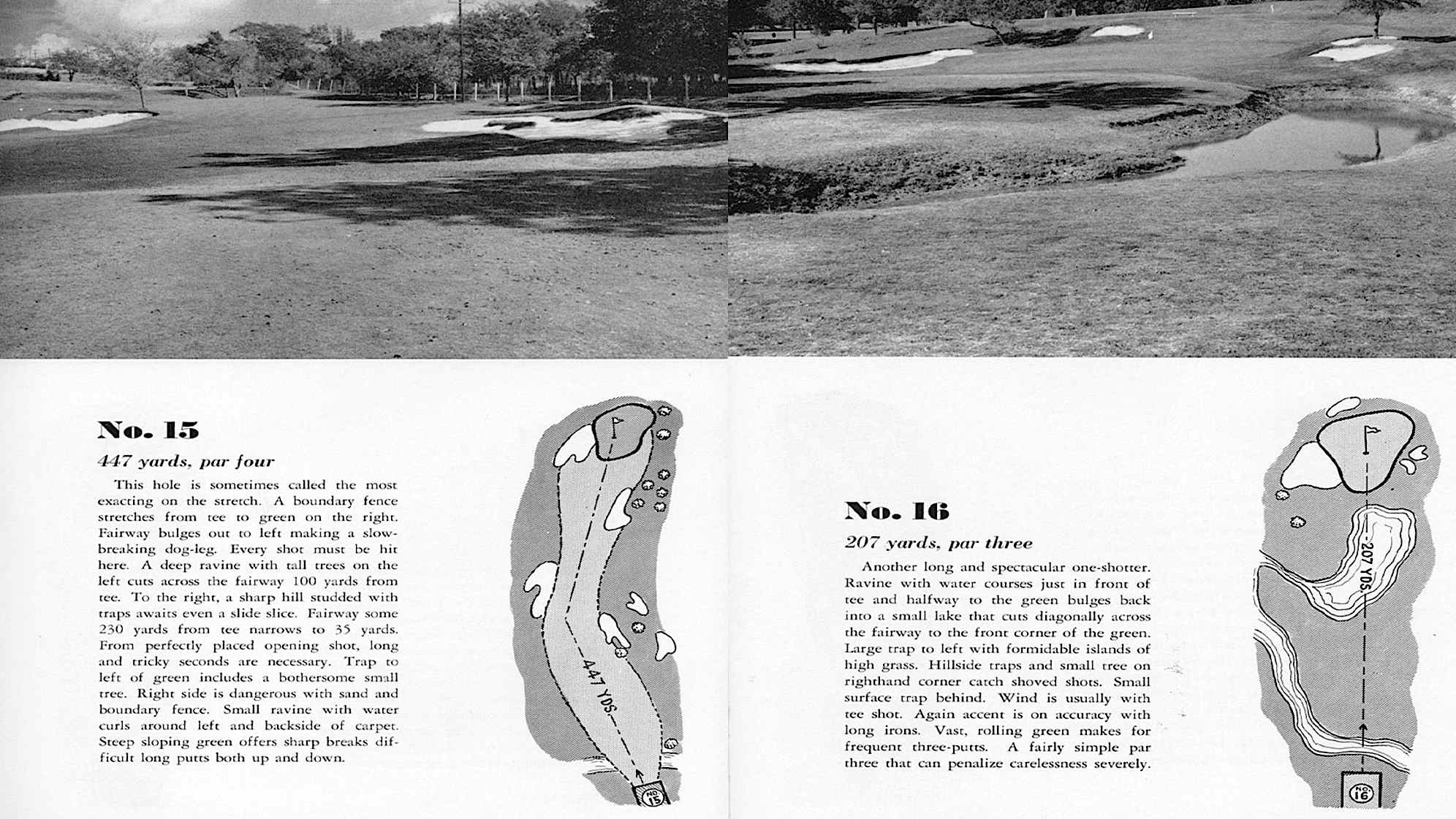

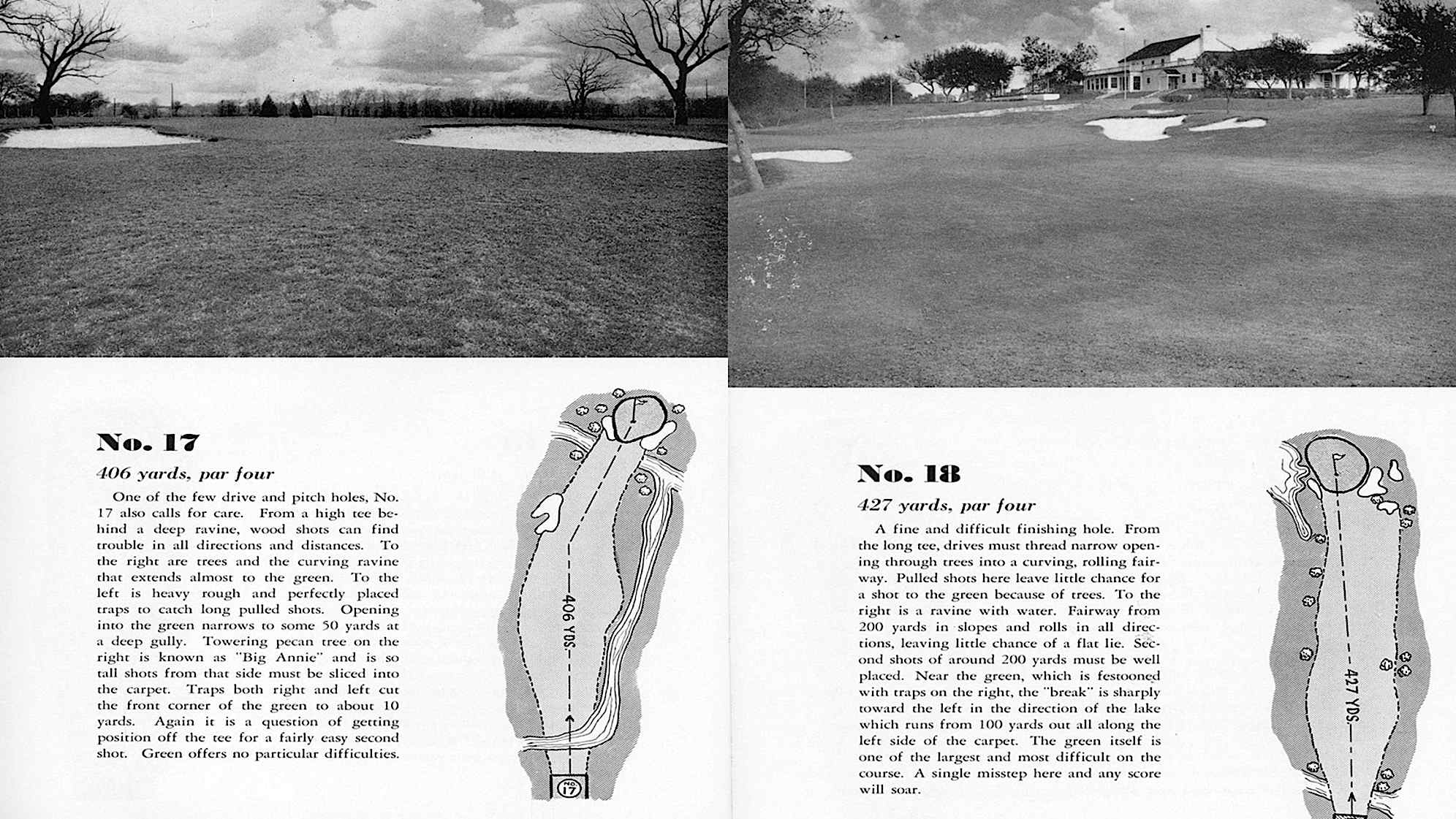

Unsurprisingly, Hanse was at the top of Colonial’s wish list. The club also had the ideal piece of history to help Hanse develop his plan – a program from the 1941 U.S. Open at Colonial. It quickly became Hanse’s north star and the key to unlocking the Colonial of yesteryear.

The program had photos of every hole and detailed a rugged Colonial much more in tune with the natural landscape. Over the years, those ragged edges were sharpened as the prevailing course conditioning trends in the '80s and '90s shifted to clean lines and neatly tended greenery. The course was perfectly coiffed but lacked the gritty character of the original design. Returning the course to its rustic roots became top of mind.

The program also declared Colonial’s par 3s some of the best in the world. That prestige was eroded over the decades as members and pros found the par 3s slowly morphed into one-dimensional holes, with most requiring almost the exact same club and shot shape. That gave Hanse another objective.

The skeleton key that helped unlock all of it was the discovery that water hazards were much more prevalent in the 1940s. That led to some of the biggest changes to Colonial.

“(The program) talked about all the water holes that Colonial has,” Hanse said. “When I first got here, I thought, ‘Well, there aren't that many of them,’ really (No.) 9, obviously 13. But then as you start to really look at the landscape and the way the water used to run through the landscape, it became much more apparent that, you know, 16, 17, 10, all these areas, 11, eight had water being an integral part of them.”

Hanse’s most noticeable change came at the par-3 eighth, which used to have the Trinity River running tight along its right side.

The original design was disrupted after a historic flood in 1949 forced the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to reroute and dam the river. The water was pushed farther away from the eighth green, eliminating the risk of potentially hitting it into the hazard. Over time, trees were planted, and the view of the river was blocked out.

Hanse shifted the green some 30 yards left, reintroducing a creek along the left side of the hole. It’s one of the few times that Hanse didn’t fully rekindle the original design, though that was out of necessity.

An aerial view of hole 8 at Colonial. (Matt Hahn/PGA TOUR)

By moving the green left, Hanse brought an existing creek into play that now hugs the left side of the hole and rekindles the hole's risk-reward nature. The hole's presence in the landscape, its clinging to a cliff’s edge and its fall down to the creek are all reminiscent of the old eighth hole, albeit with the water running on the opposite side.

The 13th hole also was affected by the Trinity's rerouting. The Trinity used to weave in front of the tee box and swaddle the green. Today, a pond guards the front of the green. Hanse lifted the hole, elevating the green by about 10 feet and moving it back to encapsulate how the green played in the 1940s. Hanse also expanded the tee box, which spans 70 yards and will create variety in how the tee shot is played.

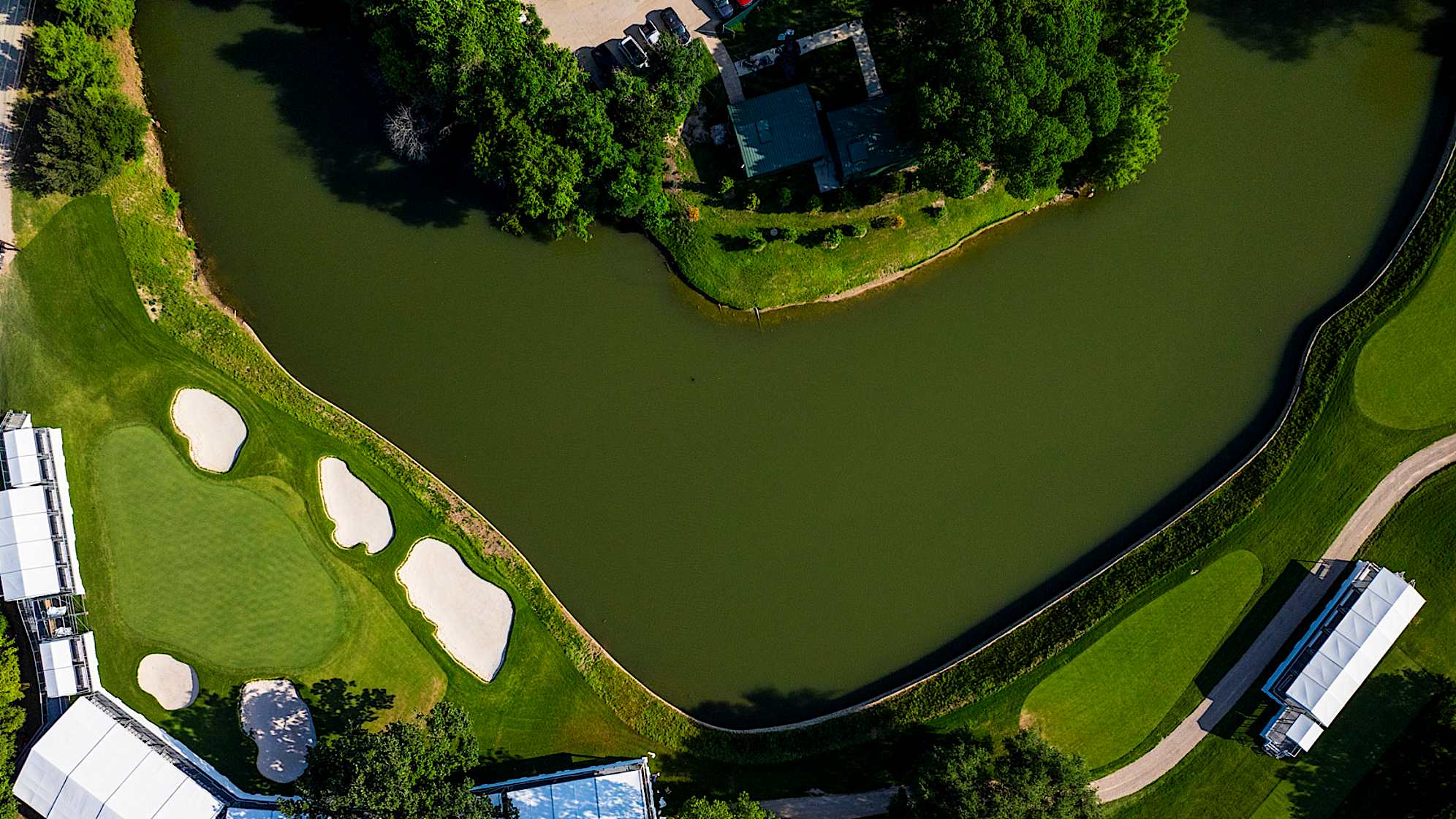

The other change that will be widely recognized is the removal of the concrete spillway that runs from the par-3 16th and intersects between the 17th and 18th fairway. Grillo famously found the area right of the 18th fairway, which caught the small current and floated back toward the 18th tee box.

Before the renovation, the concrete spillway started just in front of the 16th tee box and veered along the left side of the hole before breaking left and lining the right side of the adjoining 17th and 18th holes, which run in opposite directions. All the concrete was removed, and replaced with a natural creek bed that will render Grillo’s situation unrepeatable and spruce up the look of Colonial’s closing stretch.

“I think, without a doubt, we will be excited that CBS won't be showing any scenes of the golf ball rolling down the concrete spillway,” Hanse said with a chuckle.

The creek will still be involved in the drama of the closing stretch. Hanse moved the 16th green left to bring the creek further into play. Water now tightly guards the left and right sides of the green.

The trio of holes famously nicknamed the "Horrible Horseshoe" remained largely untouched. Colonial’s third, fourth and fifth holes were given that moniker because of their difficulty and the shape they form as they wrap around the driving range. Hanse removed greenside bunkers on the fourth and fifth holes while slightly tweaking the green contours. The left side of the fifth hole also features a shallow drop-off into a native area. Otherwise, the holes closely resemble their pre-renovation form.

“You don't want to mess with something that's already established and plays very well,” McIntosh said.

An aerial view of hole 5 at Colonial. (Matt Hahn/PGA TOUR)

It’s a sentiment Hanse handled carefully throughout the process. He made several distinct changes to the course, re-establishing the rugged aesthetic and opening up ways to make the water hazards more prevalent. The course was also modernized, with the installation of new hydronic systems that can run cold water under every green during Texas’ scorching summers. Colonial’s bentgrass greens are better suited for cooler climes, but also an important part of the club’s history.

Fort Worth businessman Marvin Leonard created Colonial because he did not like putting on the grainy Bermudagrass greens found throughout the South. He wanted a course that utilized the smoother putting surfaces that he encountered while playing in the Northeast. That’s why Colonial became the first course in Texas with bentgrass greens, one reason the club became the first club south of the Mason-Dixon Line to host a U.S. Open. The recent renovation also improved Colonial’s drainage.

The bones of Colonial remain the same, however. The corridors look familiar on almost every hole. There was hardly any tree removal or added distance, the two most prominent features in modern course renovation. Two trees died while replacing the irrigation system, but they’re the only ones missing post-renovation. A few holes were lengthened ever-so-slightly, while some fairway bunkers were moved to combat modern distance gains.

Colonial is still very much a club under construction. Though the heaviest lift – the course – is done, half of the clubhouse is gone, as is the Wall of Champions and the famous Ben Hogan statue. The renovated clubhouse will be completed in time for the 2025 Charles Schwab Challenge.

A view of hole 18 with the clubhouse behind at Colonial. (Matt Hahn/PGA TOUR)

McIntosh chuckled when asked about it. “Lucky that’s not my problem,” he said.

For the first time in the last year, he can say that. That’s for a different crew and project manager to handle.

As McIntosh looked over the course, just three weeks from the start of the Charles Schwab Challenge, he looked forward to that first exhale. Maybe it’ll come around July 4, he wonders aloud, after the tournament is finished and members can finally play. “But we’ll see,” McIntosh said.