Pete Dye: The genius who loathed plans

10 Min Read

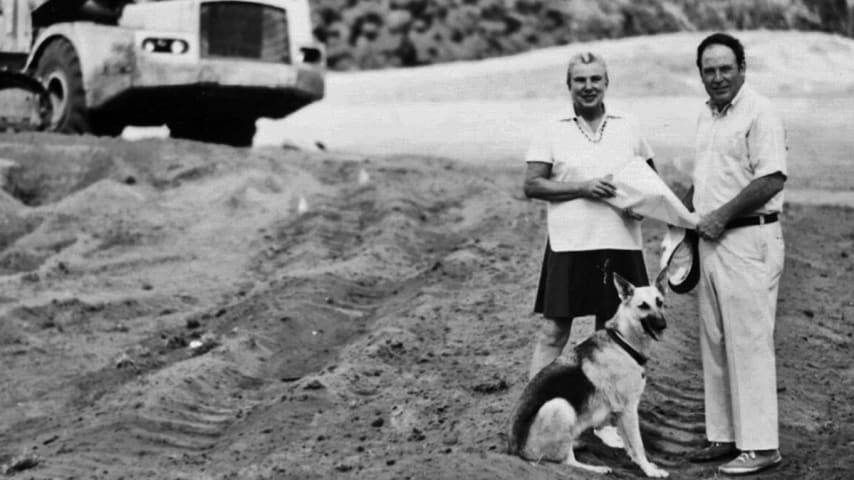

Alice and Pete Dye TPC Sawgrass - Stadium Course Construction 1980 in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida Photo by PGA TOUR Archive

Pete Dye used his barnyard engineering skills to carve out a masterpiece in the Florida swamplands

Written by Mike McAllister

PONTE VEDRA BEACH, Fla. – The bank was hesitant to approve the loan without plans, and the initial cost estimate from golf architect Pete Dye to create TPC Sawgrass did not include specifics on what the Stadium Course might actually look like.

But Dye – hired in the late 1970s by then-PGA TOUR Commissioner Deane Beman to build the TOUR’s signature course that would permanently host THE PLAYERS Championship – finally relented and drew up his vision on some nearby blueprints. “It was like pulling teeth, getting plans from Pete,” remembers his project manager, Vernon Kelly.

With those plans in place and financing secured, Dye and his team went to work. As they prepared to walk the course that first day – the only real tangible evidence of the layout were the survey lines down the center of each hole – Kelly turned to Dye and said, “Wait a minute, I forgot something.”

MORE ON DYE:Players praise Dye's legacy | Dye passes away at age 94

He made a beeline back to the parked truck they had driven to the site. Inside were those plans that Dye had submitted to the bank. Kelly grabbed the documents, then ran back to his boss, who was eager to get moving.

“What are those things?” Dye asked.

“Oh, these are the plans,” Kelly replied.

“We don’t need those,” Dye responded. “Put those back in the truck. I don’t want to see ‘em again.”

It’s a funny story that Kelly tells some 40 years later, but it’s also reflective of the approach that Dye – the World Golf Hall of Famer who passed away in January at the age of 94 – used when designing courses. Sure, he could draw up a set of plans if necessary, but most of the time he operated best when he was tinkering and constantly evaluating, and re-evaluating his work. Plans were considered guidelines (or sometimes nuisances) rather than details to be strictly followed.

He needed room for creativity, to act upon his inspirations. He needed fluidity, able to improve something at any given moment, to act on his impulses. The last thing he wanted was to be caught in a corner, hands tied, unable to make something better. He was an artist, one who enjoyed the process perhaps more than the finished product.

“Pete always said the saddest day for him was the day we had to grass a golf hole because he couldn’t tinker with it anymore,” said Bobby Weed, who apprenticed under Dye in the late ‘70s before striking out on his own. “He would tinker and he would rub on it right up until they were grassing. And I will say there’s been occasions when we’ve gone back and ripped out the grassing, ripped out the irrigation, and made a few more changes. Never say never on a completed golf course.

“If Pete had a feeling there can be something that can be improved upon, nothing was going to stop him. He had an eye that no one else had. He saw things differently, and he saw things when no one else did.”

That vision helps explains his ability as golf’s ultimate barnyard engineer, a term of endearment for people who are able to identify and solve problems simply by relying on the resources at hand. Or as industrial artist Sudhu Tewari defines it, “part science, part art and a whole lot of experimentation.”

A combination of common sense, creativity and ability to think on your feet – that seems apropos for Dye, the man with the Midwest roots who didn’t get locked in by plans and who found workarounds that become legendary solutions.

Take, for example, the iconic 17th at TPC Sawgrass, the island-green hole for which Dye is most recognized. It wasn’t originally in Dye’s initial plans (not that he was looking at those anyway). The 17th was created as a solution to solve a problem.

When Beman tasked Dye to build a “stadium” course that would allow fans to watch the action from different levels instead of standing behind each other with no gradient, the challenge was huge. After all, the swamp land that the PGA TOUR had purchased in North Florida – 415 acres for the sum of a single dollar, a bargain from most perspectives, although some, after looking at the actual land, suggested the TOUR had overpaid -- was essentially flat. There were no natural mounds to work off, so Dye had to create them.

In addition, Dye also had to cap the fairways and build the greens, adding the kind of undulation throughout those 415 acres that would test the world’s finest golfers. And he wanted to do this with his own signature design to allow any player in the field to win, as long as that player produced the best golf. That involved creating eye candy that might deceive some but certainly keep things honest on the scorecard.

The bottom line is that he needed to move sand. Lots of it. And the best sand on the site just happened to surround the current location of the 17th green. The bulldozers had their starting point.

“We kept trying to find sand to finish the course ‘cause we really didn’t have any money at that time to buy sand,” Kelly says. “So wherever we could find it, we basically used it.

“I remember very well, we got toward the end of the job and he told Alice [his wife], ‘You know, I don’t know what to do. I’ve got a 17-hole golf course here.’ And Alice said, ‘Well, you know, how about an island green?’”

Adds Beman: “By the time we took all that dirt out of there and all that sand out of there, all we had was a huge lake. And then we had to figure out, OK, what kind of hole are we going to build?

“It was originally designed not to be a complete island green, but a peninsula that had a small landing area to the left. And ultimately Pete and Alice decided that the most unique thing would be to have an island green.”

It was a brilliant solution to a sticky problem, but in this instance, Dye did not get everything he wanted. He wanted the hole to be 165 yards long. Beman put his foot down.

“We’re going to play this from about 130 yards, 135 yards, or we’re going to have a riot on our hands with our players,” Beman says. “So we came to an accommodation that has turned into being a pretty good mutual decision.”

Moving sand was one thing. Figuring out the water issues became an equally Herculean challenge for Dye’s problem-solving skills. After all, the swamp not only was flat but also, of course, full of water. Natural drainage had been cut off when the A1A By-way was installed between the course and the nearby Atlantic Ocean.

Dye had to figure out a new way to drain the area, but he simply couldn’t eliminate all the water. After all, part of the natural beauty of the location was the tree cover, and Dye did not want to lose that. He needed to find the proper balance. “If you appreciably change the water cover,” Kelly says, “you would’ve lost the trees.”

His barnyard engineering skills again put to the test, Dye found the solution with multiple miles of corrugated drainage pipes. The trees were saved, the water had a place to flow to – and Dye turned a swampland into one of golf’s most celebrated courses.

“Another one of those examples to me of just how good a designer Pete was,” Kelly says. “Drainage is one of the mechanical things that people don’t think about when they about a great golf course.”

Mechanical is one thing. Creativity is another. Beman was asked if he ever tried to get inside Dye’s mind, to understand why he designed something a certain way, why a hole was shaped or a feature added that, on the surface, might not have appeared obvious.

Beman replied that it would’ve been futile to figurer out Dye’s thought process.

“I never tried to do that,” he says. “My impression of Pete was that he didn’t work off the plans very well, didn’t like to.

“And actually, Pete Dye building a golf course is not cheap because he’s going to move dirt around until he finds what he likes to look at. And so, it’s not just of the plan and you put it here and here’s a green and here’s exactly what the elevation should be.

“He wasn’t satisfied until it fit his eye.”

His eye often included elements that other designers had never considered – railroad ties being one of his signature ingredients, a way to create visual challenges while also adding to the look of a course. As Kelly jokes, “What I heard about when I first started with the TOUR was that Pete Dye designs are the only golf courses that could potentially burn down.”

Dye’s barnyard engineering even extended to actual barnyard animals at TPC Sawgrass. Needing to rid the parcel of land of its thick underbrush and brambles and vines, as well as keep the grass trimmed in a budget-friendly manner, Dye brought in goats to handle the job.

“We would fence off a small area and put the goats in there and they would clear just about everything up to a 5-foot height that they could reach,” Kelly said. “And then we’d move ‘em to another area.”

The goats were, according to Kelly, “very effective.”

This week during THE PLAYERS Championship, there will be tributes to the man who designed this legendary course, the man who ditched his own plans to carve out a masterpiece, this man considered a “master of masking” by Beman, because he can make “a course look more difficult than it actually is.”

Dye is gone but his legacy will endure – each March when the TOUR holds its signature event, and the other 11 months when those of lesser handicaps make their pilgrimage to Ponte Vedra Beach in order to check the Stadium Course off their bucket lists. Each one will learn -- as Bobby Weed did so many years ago while working with Dye on another of his famed courses, Harbour Town – that it’s not what you plan, it’s what you do.

“He did his drawing with a tractor and a bulldozer, out in the field,” Weed says. “One of the things I really learned is don’t be afraid of changing, don’t be afraid of tearing it up and starting over. If it didn’t fit his eye, he was going to continue to shape and mold and rub on it until it felt good to him. …

“Pete always said, ‘Show me a golf course built from a set of plans, I’ll show you a bad course.’”

Forty years ago, Dye began construction on the Stadium Course at TPC Sawgrass. He sent the plans back to the truck -- and then he built one of golf’s greatest courses.

Remembering Dye at THE PLAYERS

The late Pete Dye, designer of the Stadium Course at TPC Sawgrass, will be honored in a variety of ways at THE PLAYERS Championship this week.

A permanent plaque will be unveiled on the first tee box that will include a quote from Dye: “It is a great bit of personal satisfaction to be asked by the TOUR members to build their golf course.”

Three large panels on the side of the Fan Shop will include quotes about Dye from Tiger Woods and Jack Nicklaus, along with a tribute image of the 17th hole.

Former PGA TOUR Commissioners Deane Beman and Tim Finchem, along with Bobby Weed, Jerry Pate and Vernon Kelly -- all involved in different ways in the story of TPC Sawgrass – will be special guests to discuss Dye’s legacy.

NBC, which is broadcasting THE PLAYERS, will show special vignettes to recognize Dye.

Pete Dye courses on the PGA TOUR

Thirteen different Pete Dye-designed courses have hosted PGA TOUR events:

PGA West Stadium (California), American Express

TPC River Highlands (Connecticut). Travelers Championship

TPC Sawgrass Stadium Course (Florida), THE PLAYERS Championship

Crooked Stick (Indiana), PGA Championship, BMW Championship

TPC Louisiana (Louisiana), Zurich Classic of New Orleans)

Oak Tree National (Oklahoma). 1988 PGA Championship

Nemacolin Woodlands Mystic Rock (Pennsylvania), 84 LUMBER CLASSIC

Harbour Town (South Carolina), RBC Heritage

TPC San Antonio (Texas, AT&T, Canyons), Valero Texas Open

Austin Country Club (Texas), World Golf Championships-Dell Technologies Match Play

Kingsmill Resort (Virginia), Kingsmill

Whistling Straits (Wisconsin), PGA Championship

Kiawah Island Resort (South Carolina), 2012 PGA Championship