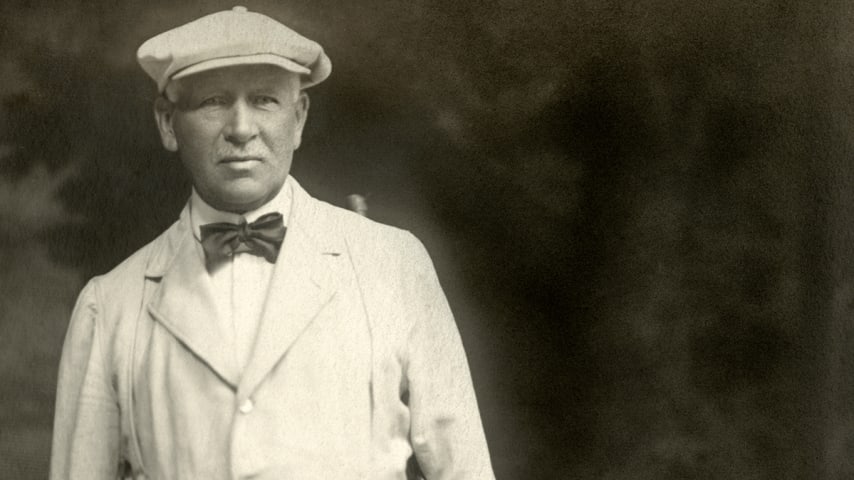

George Lyon's missing Olympic medal

15 Min Read

George S. Lyon won the last gold medal for golf in the Olympics, but it is nowhere to be found.

After George Seymour Lyon won the gold medal in St. Louis at the 1904 Olympic Games -- the lone gold medal awarded to an individual for golf until this year’s games in Rio de Janeiro -- he decided to prove to the legion of youthful doubters and fellow competitors how strong he was, despite being 46 and suffering from diabetes.

When his name was called to receive his prize, he did so upside down, having walked across the room at Glen Echo Golf Club on his hands while singing “The Wild Irish Rose” – a classic Irish sing-along tune.

The Lyon roared, and the world heard it.

He was celebrated appropriately when the Canadian returned home, but as time goes on, so do keepsakes. The iconic gold medal, signifying a huge moment in the sport’s history, was lost.

There are some theories that exist for where it could be. But to know about the medal is to know about Lyon, and the ongoing search for golf history.

It was a classic David vs. Goliath tale, that final Olympic match in 1904.

Chandler Egan, a 21-year-old Harvard graduate – and reigning U.S. Amateur champion – was defeated by the virtually unknown 46-year-old Canadian, Lyon, who had only taken up golf a couple of years prior.

The 1904 Summer Olympics, only the third Olympic games in the modern era, took place as part of the World’s Fair that year in St. Louis, and golf made its debut at storied Glen Echo.

There were numerous parts to the four-day competition (unlike the 72-hole stroke play competition to come in August in Rio) including a long-drive event. But for the medals, it came down to a match play competition between Lyon; 70 Americans, including the aforementioned Egan; and a lone participant from the United Kingdom.

Many of the competitors were half Lyon’s age, and the rain poured down during the four-day slog. But Lyon wasn’t deterred. In fact, he took it as a challenge. He drove the green on the par-4 first at Glen Echo on three separate occasions, including in the final match against Egan, where the young American was flabbergasted at his opponent’s length.

Egan was a notoriously long hitter who had captured the pre-tournament long-drive contest.

Lyon was not supposed to win.

He had a bad case of hay fever, according to newspaper reports of the tournament, and when he wasn’t playing golf, he was an insurance salesman (although anyone you speak to now will confirm that he was much better at golf than he was at selling insurance).

But he did, by a 3 & 2 score.

The numerous American competitors had offered a valiant effort, but to be fair, the best golfers from Europe were not in the field in St. Louis. So Lyon, in a typical joking fashion, told the Toronto Star after his victory, “I am not foolish enough to think that I am the best player in the world, but I am satisfied that I am not the worst.”

Lyon departed St. Louis back on a train to Toronto with both the gold medal and a grandiose sterling silver trophy in hand.

The latter remains on display in the Canadian Golf Hall of Fame, and has been making rounds in the media for the last 12 months as a lead-up to the return of Olympic golf this summer (it was at the DEAN & DELUCA Invitational at Colonial earlier this year, and Jordan Spieth made a request to see it).

The medal’s whereabouts, though, remains a mystery not yet solved by anyone – family, historians, or Hall of Fame curators.

It seems that Lyon himself may be the only person who knows what ended up happening to it. And he passed away May 11, 1938.

Before there was Tiger, there was Lyon, as Michael Cochrane likes to say.

Cochrane, a lawyer from Toronto, wrote the book on Lyon, diving deep into the Canadian’s history to try to track down the elusive medal. As he took golf up later in life like Lyon, he started to feel like the Olympic champion’s impact went beyond the golf course.

His research took on a spiritual feeling, especially as he looked into golf’s goings-on in the early 1900s.

“If it hadn’t been for these wealthy men who invested in courses and started clubs and adapted all the formal parts of the game – wearing jackets, dressing up, making it social – it may not be what it is today,” he says. “All those early clubs were founded around that time, and I felt like, when I was out on the course, I felt knowing the history made me feel like a better golfer.”

Lyon was born July 27, 1858 in Richmond, Ontario, Canada, a small town about an hour outside of the nation’s capital city, Ottawa. With golf making its Olympic return this year, the town has just recently erected a sign in Lyon’s honor (a “neat thing to commemorate and remember and to let people know in the village who might not know about it,” local City Councilor Scott Moffatt explains of the sign).

One of 13 children to Robinson E. Lyon and Sarah Maxwell, Lyon went to grammar school in Richmond, according to a 1914 edition of Canadian Golfer Magazine.

Lyon’s grandfather fought in the War of 1812, and Lyon’s father, Robinson, was the Mayor of Ottawa in 1867, the year when Canada became an independent nation from the British.

“The more I researched, the more fascinating stories I found,” explains Cochrane.

As Lyon got older, he moved to Toronto and became involved in all sports. At 18, he set a Canadian record in pole-vaulting, and he was also a tremendous cricketer.

His passion in that sport is what first prompted him to play golf.

At 38, he was playing a cricket match near Rosedale Golf Club – the host club of the Canadian Open in 1912 and 1928 - when, according to Lyon’s great-grandson Ross Wigile, golfers at the club taunted him to come across the fence from the cricket pitch to the golf course and “play a man’s sport.”

Eighteen months later, Lyon was the Canadian Amateur Champion.

“Was he a natural?” asks Wigle. “Absolutely. And of course, he was self-taught.”

Rosedale had a book commissioned to celebrate its 100th anniversary, and in it, there was a quote from Lyon about his thoughts on the game when he first took it up. He says that after his first round, like many beginners, “I caught the fever there and then.”

He was asked to join the club, accepted Rosedale’s proposition, and so began his golfing career.

Cochrane admits there was nothing in his research that said Lyon travelled to the Olympics to “stick it” to the people who didn’t believe in him – or his aggressive, unorthodox golf swing – but he was a competitor.

“He knew he was going to be criticized, and he knew people were going to make fun of the way he played golf, but he stuck to his game plan,” says Cochrane.

After the competition was completed, he wrote to a newspaper saying he was offended someone had written a story criticizing his swing. He was very sensitive about that, according to Cochrane, and thought people shouldn’t be allowed to criticize the way other people play golf.

At first, you might think Lyon’s gold medal triumph was his crowning achievement as a golfer, but he had a laundry list of other accomplishments in his homeland both before and after 1904.

He won the Canadian Amateur Championship a record eight times (between 1898 and 1914) and won the Canadian Seniors’ Golf Association Championship ten times between 1918 and 1930. Lyon also lost in the finals of the 1906 U.S. Amateur Championship, and the semi-finals of the 1908 British Amateur, when he was 50 years old.

Lyon is also a member of both Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame, and the Canadian Golf Hall of Fame, but he was also known for his off-the-course antics. Members of his other club, Lambton Golf Club in Toronto, always sing the “The Wild Irish Rose” on their opening day as a tribute to Lyon.

“He was a bon vivant (a French saying that means ‘one who lives well’),” says another of Lyon’s great-grandchildren Sandy Somers. “He was a fun guy.”

“He was a gregarious athlete, and he told a good story,” adds Wigle. “He led a great life.”

And even while busy selling insurance and competing in golf at the highest of levels in that era, he was still a devoted family man.

“He was a wonderful grandfather, a real character,” recalls Mary Lou Morgan, one of Lyon’s grandchildren, and the closest living relative to Lyon himself.

Morgan remembers having Sunday tea every week with her grandparents, including Lyon, and he would bounce her and her siblings on his knee. She says the grandiose Olympic trophy would be ever-present on Lyon’s dining room table, but doesn’t recall the Olympic medal itself.

“Little did we know what it was worth,” she says. “But he was a real grandfather, and it was just wonderful to have known him.”

So without the immediate family knowing where it is, and with it not in the Canadian or World Golf Hall of Fame, where could that medal be?

Chandler Egan was the preeminent amateur golfer of his time, a Jordan Spieth-type, according to many historians, and when he arrived in St. Louis in the summer of 1904, it was almost a foregone conclusion that he would leave town with the gold medal.

That was, of course, not the case. But Egan did win silver for his troubles, along with gold in the team portion of the competition.

And more than 100 years later, those medals came back into existence.

Some members of the Egan family were cleaning out the house of their mother, who had just passed away. In the attic of the home was a small filing cabinet, and in the cabinet, there was a little box.

“They opened it up, and there they were, low and behold. The gold and silver medal of Chandler Egan,” says Brodie Waters, the Senior Director of Institutional Advancement at the World Golf Hall of Fame, where the medals now reside. “They hadn’t seen the light of day in 70-plus years, as their mother never told them she had them. The family knew a little bit about their grandfather, but they weren’t exactly close to him. They knew of his successes, though.”

Waters worked with other governing bodies of the sport to pull together a travelling Olympic exhibit, and the medals are a key attraction.

“The Olympics are such a huge, global phenomenon. It’s bigger than the game of golf,” explains Waters. “It’s really unique to see medals or artifacts from more than 100 years ago. They’re in phenomenal shape, and having the medals have been really well-received.”

Somers feels like this situation may happen with his great-grandfather’s medal, although he is happy to still have the large trophy in the public eye to signify the victory.

Wigle isn’t as optimistic, but is a bit of a hopeless romantic.

“I’d like to think it was melted down and there is a little piece of that medal in a thousand different wedding rings now,” he says with a smile.

And just as Wigle has a romantic feeling about Lyon’s medal, so does Cochrane.

“I’d like to hope his wife tucked it into his pocket for his burial after he passed away,” he says. “That would have been a nice way for the medal to be passed on.”

A popular running theory is that the medal, which would have looked more like a participant award as opposed to the fabulous medals that are handed out to Olympic champions in more recent times, was more of a trinket, and could have been lost, given away for nothing, or sold for money during the Great Depression in order to help put food on the Lyon family table.

“The chances of it being out there is slim, but it’s a possibility,” says Jared Stapleton, a coin dealer that specializes in coins and tokens at Metro Coin and Bank Note in Toronto. “(Lyon) was paying for himself to go to the Olympics and paying for everything himself, so that’s probably where the medal went – to pay for things.”

Although the medal’s whereabouts remains uncertain, the trophy (“the really big prize,” according to Wigle) is in very capable hands.

“When Lyon got his medal, after winning trophies, cups, bowls and serving trays, he probably saw it and thought, ‘meh’,” says Canadian Golf Hall of Fame curator Meggan Gardner.

The trophy, handcrafted by J.Bolland (a company that no longer exists) is a significant piece in itself. But the Lyon family still tried their best to get a medal in their possession.

According to Gardner, the Lyon family, along with the Canadian Olympic Committee, reached out to the International Olympic Committee to try to get Lyon’s gold medal recast. The IOC has only one medal from 1904 in their possession, a track and field medal, and said they would indeed duplicate that one (at a minimal cost, Gardner estimates it was less than $1,000).

The best the IOC could do was erase the event name (it was for the 800-meter event) and replace that with the word “golf.”

“They agreed and thought that was fair, so it was recast and remade, and donated to Rosedale to put on display,” says Gardner. “It was a huge favor they were asking, but it was a special circumstance and the IOC did it.”

Gardner says Lyon’s medal, if it ever was found, would easily double the value of Egan’s medals (approximately $20,000, she says) but it’s a little less of a rarity now, with Egan’s medals being uncovered.

“The value would probably be higher if Egan’s medals were never found,” she says. “We didn’t know any of these existed, but now we know they do, so it’s a little less rare.”

Lyon nearly repeated his gold-medal winning achievement in 1908, but after arriving in London to defend his title, it was announced the golf competition would be cancelled as the British and the Irish couldn’t decide on the proper definition of “amateur” and both pulled out.

After the British and Irish said they weren’t going to play, the Americans also withdrew. Lyon, who was 50, had all his paperwork in line and was ready to play. They offered him the gold medal without competition, but he turned it down.

Wigle says Lyon felt a competitor should only ever win through competition, on the grounds that golf was a gentleman’s sport.

Lyon went back to selling insurance at his own company, called Lyon & Butler, and continued to play amateur events in Canada. But when the depression rolled around 20 years later, Gardner thinks there would have been a demand for his company’s assets. With Lyon’s passion being more so on the golf course than the boardroom, Gardner feels that selling the medal is likely what happened.

She remains stumped as to why Lyon didn’t melt down the Olympic trophy instead – there would have been much more money in the silver he got from that versus the small amount of gold – but she feels Lyon was too proud for that.

“If he didn’t see the medal as being as valuable to him as the trophy, then yes, he probably got rid of the least important things in his collection,” she says.

For capturing three Canadian Amateur titles in a row, Lyon was also awarded the Aberdeen Cup by Lord Aberdeen himself, and got to keep that trophy outright. Gardner says that trophy is also missing, and the family doesn’t know what happened to it.

“He may have sold off a few pieces from his collection of golf winnings for financial gain,” she states.

For capturing three Canadian Amateur titles in a row, Lyon was also awarded the Aberdeen Cup by Lord Aberdeen himself, and got to keep that trophy outright. Gardner says that trophy is also missing, and the family doesn’t know what happened to it.

“He may have sold off a few pieces from his collection of golf winnings for financial gain,” she states.

With Lyon’s golden mystery still ongoing, there are many who are happy to see some remnants of the past still in the public eye, like Lyon’s trophy and Egan’s medals.

It’s difficult to image this year’s Olympic champion will traverse the stage in Rio on his (or her) hands while belting out a song meant more for pubs than country clubs, but knowing Lyon’s game and unusual swing, perhaps there would be a chance for history to repeat itself in terms of the kind of winner Rio produces.

Ian Andrew, a Canadian golf course architect who spent some time with Gil Hanse as he built the course in Rio, says a “fearless” kind of golfer will be come out as the gold-medal winner.

But don’t count out the underdog, either.

“You’re talking about a 20-year-old who was highly favored to win, and then there’s this 46-year-old that no one had known anything about,” says Waters of Lyon’s Olympic victory. “He drove the green on the first hole in the match against Egan, and that threw him off for the match. The rest is history.”

History, as they say, has a funny way of repeating itself, especially in golf.

If only golf could produce a golden historical artifact, then the world could hear Lyon’s roar, one more time.