Stuart Appleby details his journey through grief before winning 1999 Houston Open

7 Min Read

Stuart Appleby posing with the 1999 Houston Open trophy. (Bob Strauss/PGA TOUR Archive)

Written by Stuart Appleby

Almost walked away from golf after death of wife Renay in 1998

Editor’s Note: During his 23-year PGA TOUR career, Stuart Appleby won nine times. Two of those victories were at the Houston Open, in 1999 and again in 2006. His first Houston title came nine months after Appleby became a widow following his wife’s untimely death in England in the summer of 1998. On the 25th anniversary of his win at TPC Woodlands, Appleby reflected on that period of his life, when he briefly considered walking away from the game but ultimately decided to continue and then went on to win in Houston.

In the spring of 1999, there was a lot on my mind, and most of it had very little to do with golf. I actually don’t remember a lot of specifics about my Houston Open win that year other than just how hard TPC Woodlands was. I won the tournament at 9-under, beating John Cook and Hal Sutton by a stroke.

More importantly, that was also my first PGA TOUR victory since my wife, Renay, died a year earlier in car crash in London. There was a time after the accident that I wasn’t sure I wanted to continue playing.

As I look back, I know I came really close to quitting golf. In August, about a month after Renay died, I was back in Australia, and I just remember feeling in my soul, telling myself that I would never play golf again. I was done. And it felt real. When I thought it, whether I said it loud I don’t know, but it honestly felt like a truthful statement, a fair call.

I just wasn’t interested, and I didn’t want to play golf anymore. My reasoning was I didn’t have the person I was supposed to share my career with. So, what was the point?

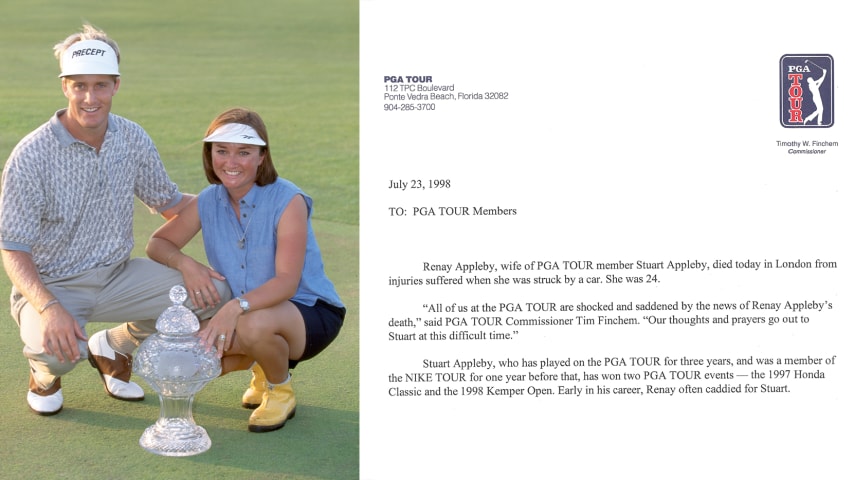

On the left, Stuart Appleby and the late Renay Appleby pose at the 1997 Honda Classic. On the right, a letter sent to PGA TOUR members in 1998 concerning the death of Renay Appleby. (PGA TOUR Archive)

I can’t put my finger on anything specifically that changed my mind, but not long after that critical juncture, I knew the PGA Championship at Sahalee Country Club outside Seattle was coming up in mid-August, and those retirement thoughts suddenly disappeared. I decided I was going to play, and I did. I don't remember much about that week in Sammamish, Washington. I know I did a pre-tournament media interview, where I looked disheveled and just beaten down. And that’s pretty much how I felt. I missed the cut that week, but the PGA started my climb out, which was, perhaps, therapy through playing. The next week, I played in The International in Denver and the NEC World Series of Golf in Akron after that.

Then I went back to Australia, where things started to brighten even more. I finished second at the Australian Open in early December, losing to Greg Chalmers at Royal Adelaide, and I was part of the International Presidents Cup team that beat the U.S., at Royal Melbourne. I went 2-1-1 in my four matches.

The good stretch continued, the gloom continuing to lift. I won the Coolum Classic in Australia, right before Christmas, five months after Renay’s death. For sentimental reasons, I played in that tournament because Renay loved the place. I shot a 63 in the third round and went on to beat Craig Spence by four shots. My parents were there, and a few from Renay’s family were also in attendance, which made it even more special.

One thing on my mind was that wherever I went, I thought of the people I met, knowing that it must have been quite uncomfortable for them because I knew they didn’t know what to say to me, and I didn’t know what to say back. Truthfully, so much of that time in my life is a blur. Golf really did help pull me out of the anguish I felt.

I think that’s why Houston ended up meaning a lot to me six months after Coolum because that was a win on the PGA TOUR, the best Tour in the world, against proper, veteran players. I had to hold off Cook and Sutton at the end in a tournament that also featured so many other great players.

TPC Woodlands was a terribly challenging course, and I only broke 70 one day (a second-round 68). I shot a pair of 70s in the first and third rounds and entered the final round three strokes behind Hal.

Sunday mid-morning, I was on the range doing my normal work when Ken Venturi stopped to watch. He was there for the CBS broadcast. I was hitting it pretty well, playing nicely, and as I wrapped up my session, Ken said, “If you hit it like that, boy, you’ll win.”

Here was this absolute broadcast legend, a legend of the game, really, saying what he said, and I was like, “Oh, okay, thanks, Ken, for that bit of pressure.” But it was a nice thing to hear, and I don’t know if that had anything to do with how I played that day, but I got off to a quick start, making birdie on the par-5 opening hole. By the time I made the turn, however, I was 1-over for the day, with a couple of bogeys.

Although I only made two birdies the rest of the way, one was crucial, a 15-foot putt at the par-4 17th that gave me the lead. Playing in the group behind me, Hal made back-to-back bogeys, on 16 and 17. I parred 18, and when Hal missed a birdie putt on his closing hole that would have forced a playoff, I had the win.

In my post-round media conference, naturally the press asked me about Renay. I credited her, telling the reporters that she gave me strength not only that day but that whole week. I also remember saying that she was going to be with me forever in whatever it was I was doing; not just golf.

Something else I appreciated was Hal taking the time to tell the media after the tournament something to the effect that it was my time to win, and if someone had to beat him, he was happy it was me. He said he understood how much this victory meant and that he was sure there was someone smiling down on me. That was incredibly nice and generous of him to say.

I love to play golf, and it’s fun to win. Yet, what I’ve learned is it’s relationships that are important, and that’s why Houston was significant to me. That win, that week, reminded me of Renay, who, before her death, was always pretty much with me. She caddied for me and was a good player herself. She taught the game and comprehended the nuances and the psychology. I could talk to her about things, and she understood.

Then she was gone, and suddenly death was a very personal thing. How are you supposed to feel when someone close to you dies?

I have a rough idea.

We were just into a marriage relationship, just getting our lives going. Then I think about people who lose a spouse after 50 years, and I would think, That’s so good. At least you had 50 years. Then I stop and ponder it more. Losing someone after 50 years must be so difficult.

I keep that in mind and realize that one thing that got me through my tragedy was I tried to look at it knowing there are people who have a worse story than me—whatever that story is—and they’re doing it harder than me.

Victories are nice on a personal satisfaction level but only for a fleeting moment. You hold a trophy for five minutes. It’s nothing much else after that. But when you’re on your deathbed, you’re not going to say to your children, “Oh my gosh, do you remember that putt I made on the 72nd hole back 50 years ago?”

There are much more important things in life.