Late best friend inspires Jimmy Stanger in Valspar Championship homecoming

6 Min Read

Jimmy Stanger (right) poses with late friend Harris Armstrong (left) and Harris' younger sister Alison (middle). (Courtesy of Teri Stanger)

Rides resiliency to hometown TOUR event

Written by Kevin Prise

Rides resiliency to hometown TOUR event

Last summer, Jimmy Stanger earned his first Korn Ferry Tour title at the Compliance Solutions Championship in Oklahoma – one week after entering the final hole in Wichita tied for the lead but closing with a quintuple-bogey 9.

It was a remarkable level of resilience, but it didn’t come as a surprise for his childhood friend Danny Walker, a Korn Ferry Tour pro. Far from it.

“He’s just someone who would bounce back from a setback,” said Walker, who recently lived with Stanger for two years outside Jacksonville. “He wouldn’t let it deter him for too long.”

That win in Oklahoma propelled Stanger to his first TOUR card and a spot in this week’s Valspar Championship, where he’ll compete in his hometown TOUR event for the first time as a member. Stanger grew up attending the Valspar, volunteering on the range and as a standard bearer, particularly enjoying the action at the double-dogleg, serpentine par-5 fifth at Innisbrook Resort’s Copperhead Course. He remembers Rocco Mediate asking what types of shots he’d like to see on the range, and Jerry Kelly asking thoughtful questions about his life.

Stanger’s childhood fan experiences are framed by Tampa Bay Buccaneers, Rays and Lightning games and trips to the Valspar Championship. This week, he’ll relish the chance to compete in his hometown TOUR event, as a TOUR member, in front of dozens of family, friends and fans.

One person, though, is missing.

Stanger’s childhood best friend Harris Armstrong died Dec. 1, 2008, at age 12, after being diagnosed with astrocytoma (a spinal cord tumor) in October 2007. Their friendship was such that “it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say we hung out every day from age 6 to 13,” Stanger said last week; after a few years of friendship, the Armstrong family moved to the same suburban Tampa neighborhood as the Stangers. They’d volunteer together at the Valspar; they’d play junior golf events together; their competitive bent included everything from ping-pong to hide-and-seek. Their golf results were an even 50-50 split, said Stanger, who was always impressed with Armstrong’s short game.

“The biggest thing I learned from him was to use your feel around the greens a little more,” Stanger said of Armstrong, who was a two-time national finalist in Golf Channel’s Drive, Chip and Putt. “Just chip like Harris.”

Jimmy Stanger (left) and late friend Harris Armstrong (right) on a tee box. (Courtesy of Teri Stanger)

Stanger marks his golf balls with “H.A.” before every competitive round. His wedges are stamped with “Pray Strong and “Romans 12:12,” phrases used on bracelets to support Armstrong during his fight. Sometimes he’ll point to the sky after a birdie and think of his childhood best friend.

“I don’t think I’d be a professional golfer today without that,” Stanger said, “because it gave me a seriousness and a sense of purpose to everything I did. Today, I still hope that I’m playing for him … I have no doubt that Harris would still be playing golf today and had the talent level to be out here for sure. Harris has made a big impact in my life, still lives on today in my mind.

“I know I owe a lot to Harris.”

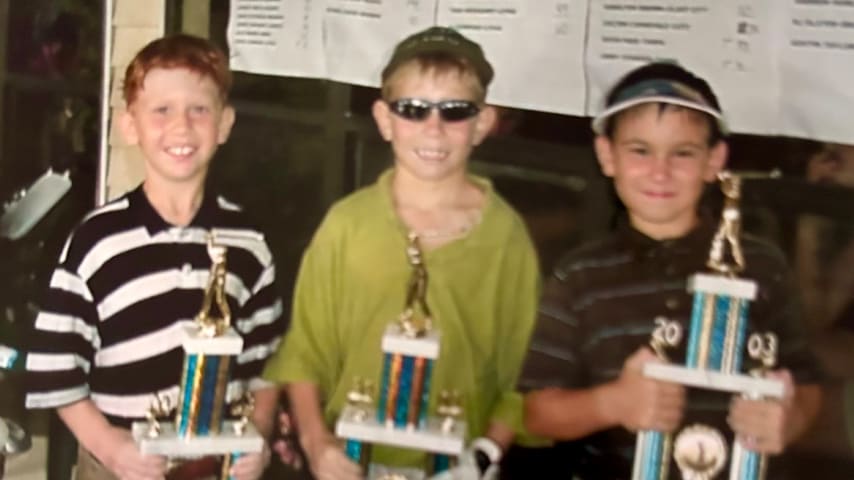

Jimmy Stanger (center) and late friend Harris Armstrong (left) hold trophies after a junior event. (Courtesy of Teri Stanger)

Stanger remembers the initial symptoms. Armstrong, who played golf righty but was naturally left-handed, started having trouble making a basketball layup with his left hand. There was a time at the chipping area when Armstrong told Stanger that he didn’t feel right, which Stanger remembers to this day.

Shortly after Armstrong was diagnosed, Stanger dedicated his seventh-grade golf season to his best friend, immediately beginning the practice of marking his golf balls with Armstrong’s initials. Stanger visited in the hospital often; Armstrong enjoyed watching football and playing tennis and golf games on Nintendo Wii – still honing his swing, just in virtual fashion, wrote the Tampa Bay Times in 2007.

Armstrong’s battle had gained traction to the point where Tiger Woods, among others, reached out and sent items for encouragement. Despite the shock of Armstrong’s passing, there was a sense of gratitude at the funeral as a tribute to the redhead’s positive energy.

“He was one of the happiest guys you’ll ever meet,” Stanger said. “Competitive but joyful, always had a smile on his face … I also saw the impact that Harris’ story had on others, and I saw how God used that to impact so many others for good.

“His funeral, I’ll never forget … There were thousands of people there, talking about different ways Harris impacted them and gave him hope, made a difference in their life.”

Jimmy Stanger (second from left) and late friend Harris Armstrong (left) with a group of friends at the golf course. (Courtesy of Teri Stanger)

Stanger’s foundation, Birdies For Hope, focuses on building churches and hope centers in third-world countries, with nine having opened so far. Stanger donates $20 per birdie to the cause, intent on using his platform as a TOUR player to inspire others and make a difference across the world.

“A lot of these villages don't have the traditional charities that we have here, so these buildings double as orphanages, they double as hospitals, they double as schools for children, and they really fill these necessary needs that give hope to those communities,” Stanger said Tuesday.

“The golf life is amazing, there are so many perks to being a professional golfer on the PGA TOUR, but in the end, it's far better to give back to the community than to receive all these gifts.”

There might be a day he’s well outside the cut line with a few holes to play, little chance to advance to the weekend, but the knowledge of helping Birdies For Hope just that extra bit can make a difference – with the momentum spinning forward into the next week.

Golf’s margins are small – Stanger made an 8-footer to make the cut on the final hole of his second round at the Cognizant Classic in The Palm Beaches, having waited all night to attempt the putt Saturday morning. He proceeded to finish T35 and earn the last spot in last week’s field at THE PLAYERS Championship (he also finished T35).

Jimmy Stanger spins wedge to 3 feet and birdies at THE PLAYERS

Success comes on those margins, which Stanger has always appreciated, as his dad James remembered last week. One year at the Valspar, father and son watched Vijay Singh work through one of his famous driving-range grind sessions. Some kids might be discouraged by the level of commitment required to sustain a high-level professional career. Not Stanger.

“(Singh) would hit ball after ball after ball, and I’d never seen anyone hit so many balls, and neither did Jimmy,” recalled James Stanger. “And he goes, ‘Dad, he just keeps hitting and hitting. I want to do that someday. That’s how you get good.’”

Stanger and Armstrong were kindred spirits in this regard, pushing each other to get good. Then everything changed. Stanger took Armstrong’s passing “very hard,” James Stanger told the Tampa Bay Times in 2017.

Yet evidenced by the emotion in the normally mild-mannered Stanger’s voice when speaking last week, the bond remains strong nearly two decades later. Stanger keeps it with him, this week and always.

“I was 13 years old at the time; that’s kind of the age where you’re starting to remember things,” Stanger said of Armstrong’s passing. “You’re starting to realize that life is more than just you; you’re starting to be aware of other people, and I realized quickly at the time that this world’s a whole lot more than just about golf. It’s a whole lot more than just about things that make me happy, and that life can come at you fast.”

Birdie or quintuple bogey, it doesn’t much matter in the grand scheme. But the human connection endures forever.