Arnold Palmer tales keep his legacy alive

16 Min Read

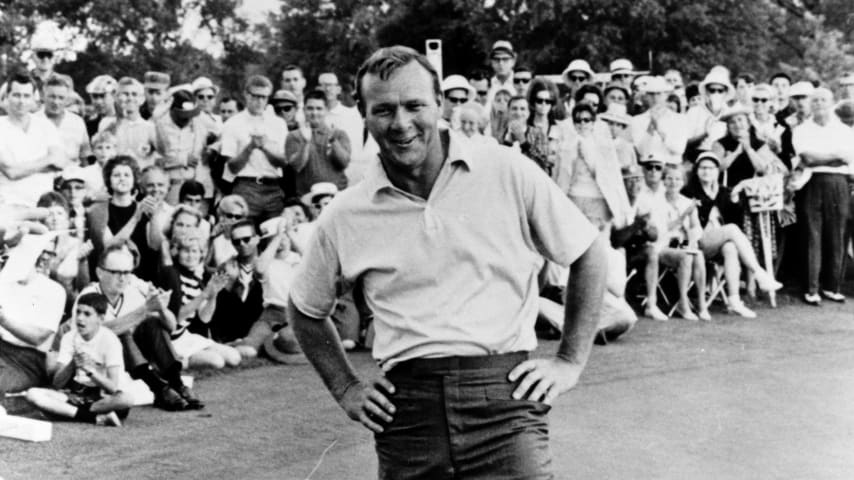

At Bay Hill, the entertaining Arnold Palmer stories live on, much like the legacy of the man

ORLANDO, Fla. – The Arnold Palmer Invitational presented by Mastercard tees off on Thursday morning featuring 44 of the top 50 players in the Official World Golf Ranking, the strongest field in the event’s history. You know who would have loved that? Arnold Palmer, for sure.

He always wanted to see the best players take on a tough test of golf. This will be the seventh year of the Arnold Palmer Invitational forging on despite the absence of its namesake, the omnipresent tournament host who passed away in the autumn of 2016. Palmer’s presence remains everywhere at Bay Hill, though, from the umbrella logos and his bag on the practice tee to the many inspirational sayings from Palmer sprinkled across the property.

Palmer’s spirit, and legacy, live on through his tournament. To rekindle warm thoughts of the man, here are a few Arnie tales from some folks who knew him better than most.

Billy Andrade grew up in Rhode Island, not exactly a golf hotbed, but had a nice junior career and was an attractive recruit for many of the nation’s top colleges. Funny, though, he made only one recruiting visit, that being to Wake Forest in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, which is where one Arnold Daniel Palmer once played.

Andrade: “My first and only recruiting trip was to Wake Forest, and Coach (Jesse) Haddock offered me the Arnold Palmer Scholarship, and that was it. I was one and done. To get his scholarship, I didn’t know at the time what it would mean. But for 35-plus years, to enjoy the friendship I had with him, the time I had with him, the memories, the golf rounds, to chance to see him as a role model. He took a liking to all of us. Being one of his boys at Wake Forest, it was pretty special. It was an honor to be a part of it. Curtis (Strange), Jay (Haas), Webb Simpson and myself, and many in between. He always kept tabs on us.”

For six or seven years later in his career, Andrade had a tradition where he would arrive to Bay Hill on Monday afternoon, scale the steps up to Palmer’s second-floor office, and duck his head in. “Are you ready?” Palmer would ask him. “Let’s go.” And the two would head off to play the back nine together, just the two of them.

One year, Andrade got a new Blackberry phone, and he inserred Palmer’s number in there, under his initials, AP. (That number remains in Andrade’s phone today.) Problem is, for whatever reason, Andrade's new phone would mysteriously “pocket dial” people. The person that Andrade always seemed to dial up, mostly unbeknownst to him, was AP.

“I hung my jacket up in a closet one time, closed the door, and all of a sudden I’m hearing Arnold’s voice, screaming, “BILLY! BILLY! DAMMIT BILLY, I KNOW YOU’RE NOT TRYING TO CALL ME!”

Adds Andrade, "Do you how strange that is, to hear Arnold Palmer’s voice coming out of your closet?”

Steve Stricker played Palmer clubs in his early years on TOUR – “I still have the irons, with the little ‘wingback’ on the shaft, a nice set,’ he said recently and had a nice showing at Bay Hill in 1995, his second year on TOUR. He finished fourth.

On the Monday after, Stricker and his wife, Nicki, who was caddying for him, stayed in Orlando, and drove over to Bay Hill to see if Palmer was in his office. They figured they would say a quick “thank you” for what had been a terrific week and soon be on their way. There was nothing quick about the visit.

Stricker: “He’s in his office, and he sees us and says, ‘C’mon, sit down.’ It was literally like talking to your Grandpa. He started pulling out some of his news clippings and articles. Doc (Giffin, Arnold’s assistant for 50-plus years) was there. Arnold pulled out this memorabilia book, and Doc would keep track of every round.

“I get goosebumps thinking about it. It was Nicki and I, and we just sat there in our two chairs and listened to Arnold talk about the 1950s and ‘60s. I’m just a new guy on Tour. That was one of the coolest things, and we remember it to this day.”

Paul Goydos showed up to to play the 1994 U.S. Open and had planned to play a quiet practice round on Monday, before the big latter-week crowds showed up to Oakmont. Bob Friend, who was an Oakmont guy, was playing, and the third player in the group that day turned out to be another Pittsburgh local: Arnold Palmer. It would be Palmer’s final U.S. Open, contested at a venue where he nearly won in 1962, losing to Jack Nicklaus in a Monday playoff.

Goydos: “It’s only Monday, and maybe I’m exaggerating it ... but it seemed that there were thousands of people following us. Thousands. That’s what it felt like.

“The quality that Arnold Palmer had that I’ve never met anyone else who had – at least in our sport – was that everybody in that crowd felt, at one point, that he looked them in the eye. He gave the impression that everybody there, he knew you were there. That’s a skill that I don’t have. It’s something.

“To me, that was always my definition of Arnold Palmer. He could go to Muirfield (in Scotland), one of the most blue-blooded of blue-blooded clubs, and fit in like a champion, and then go to the muni course in Long Beach (California) and fit in like a champion. Everybody related to Arnold Palmer, and that’s not true of anybody else in our sport.”

Goydos had his first PGA TOUR victory at Bay Hill in 1996. Seeing that his best finish to that point was a seventh-place showing at the Bob Hope, Goydos winning the title came as a bit of a surprise.

“When I came up 18, Johnny Miller (working for NBC) said, ‘This guy doesn’t have the record to win at Bay Hill,” Goydos recalls. “All wins are special. That one was pretty cool.”

Rocco Mediate started the 2007 season as a walking reporter on television, not sure what he was going to do after fighting injuries the previous season. He still was exempt into the L.A. Open, and he decided he’d try to play.

First day of that tournament, Palmer phoned him from Orlando. “You’re not in MY tournament,” he told Mediate, as Bay Hill loomed just weeks away. Mediate responded, “I know I’m not in your tournament.” Palmer offered an exemption, ‘No, you’ve already done that for me. I’m good.’"

Mediate made Palmer a deal. If he played nicely at Riviera and then Honda, give him a call. ("Arnold loved that stuff," Mediate said.) Then he tied for ninth at Riviera. A Pittsburgh kid who grew up idolizing Palmer, Mediate picks up the story:

“I get back to the house after Riv. Phone rings. It’s AP. ‘Yes sir. Tuesday morning at Bay Hill. Practice round. Yes, sir. See you then.’”

Mediate headed to Bay Hill on 11th-hour sponsor exemption, and plays great. He finishes up on Sunday, and it appears he might be in line for a second-place finish, which is big for him at the time. Vijay Singh was still on the course, cruising to what appeared to be an easy victory.

Doc Giffin tapped Mediate on the shoulder. “Boss wants to see you in the cabin,” Doc tells him.

Mediate joined Palmer in the small cottage that sits next to the 18th fairway at Bay Hill. Palmer greeted Mediate with an enthusiastic thumbs up and a “Great playin’” and pours him a scotch to celebrate. Singh makes a bogey. Then another. Mediate has arrived to the bottom of his glass of scotch, Palmer pours him another. .

Mediate: “Now Vijay is on the 18th hole with like a two-shot lead, and you can make a 6 (double bogey) in a heartbeat on that hole. Vijay drives it right, has to lay up. Now I’m thinking, 'I could win this thing,' which would be fine – no disrespect to Veej. But now I’m thinking, ‘What if I tie?’ I looked at Arnold, and I say, ‘Mr. Palmer, would you be able to drive me out if there’s a playoff? Because I’m toast.’ He says to me, ‘Well, you should have stopped.’ And I tell him, ‘You’re watching the same thing I am, and you kept pouring!’ Vijay knocks it on the green, and he wins. It was pretty funny. Mr. Palmer was my guy. He was my favorite.”

Woody Austin said when he earned his card at Q-School and stepped out onto the PGA TOUR, he made it a point to try to play with Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus as much as he possibly could. Austin played well enough as a rookie to earn his way into Palmer’s invitational event, where he approached Palmer to ask this: if he got into Augusta, could the two of them talk? When Austin got an invitation to the 1996 Masters, he made his request more formal: Any possibility that I might play a practice round with you, Mr. Palmer?

“He looks at me,” Austin says, shifting in a low, Palmer-like voice, and he says (grumbling), “I play on Tuesday mornings.”

So off they went on Tuesday morning in April 1996.

Austin: “We got up on 16, the par 3, and the pin was back right, which is normally the Masters’ Saturday pin placement, up on that shelf. He looked at our group on the tee and says, ‘Guys, you don’t hit no high cut into this ... everybody wants to hit a high cut. No, no, no. You hit a low draw, and you chase the ball up the slope.’

“Then he pulled out a 4-iron and hits a shot to about 6 inches. And the place just went absolutely bonkers. He repeats to us, ‘That’s how you play the hole. No cuts.’

"That was what you want. You want your first experience .. hey, just being at Augusta is unbelievable, but to be there with one of the all-time greats? That’s how you want to play Augusta. And that’s how I got to play Augusta.”

Tom Lehman had some close calls at Bay Hill – he lost in a playoff one year – but never did earn the champion’s sword (now a red cardigan sweater) at Arnie’s Place. Lehman did get to play for Palmer in the 1996 Presidents Cup. Lehman was seated next to Palmer at the Opening Ceremony, where Palmer and International captain Peter Thomson of Australia would give speeches to kick off the event. Lehman was seated next to Palmer as Thomson spoke first.

“They must have had some sort of a contentious relationship, or were really competitive in some way. I think Peter knew how to push Arnie’s buttons,” Lehman said, laughing, “and the whole speech that Peter was giving, Arnold was muttering to himself, which was private, but funny. He was so competitive.”

Lehman recalls walking down the hallway one day during that Presidents Cup, early afternoon, with his wife, Melissa. Palmer was walking toward them, with a can of beer in his hand. It was 2 p.m.

“And my wife says, ‘Arnie, isn’t it a little early to be drinking?’ And Arnold says, “I’m not drinking. It’s only beer.’”

There always was a level of consternation about what might happen to Arnie’s event in Orlando once he no longer was there to host. Lehman never worried too much about it, knowing Bay Hill would be fine. Just look at this week’s stacked field.

Lehman: “Arnold is such a larger-than-life character. His legacy is so powerful. What he is going to mean to the game is never going to go away. With good management up top, keeping alive the principles by which he played and lived ... he was very principled. There was a right way of doing it, and a wrong of doing it, and if you weren’t doing it the right way, he’d let you know. He wanted people to respect the game and respect the competition, and to do it right.”

When he competed at Bay Hill, Jason Bohn liked to take his sons so that they could watch, and meet, Arnold Palmer. Pretty cool.

Bohn was playing a practice round at Augusta National for the Masters one year, and he sprayed his tee shot on 18 well right into the trees. There were two Augusta Natoinal members in green jackets up ahead of him in a cart, and Bohn, trying to find a way to extricate himself from the trees, waved at them to move, as they could be in harm’s way of his next shot.

So the cart wheeled around and headed back toward Bohn, and in it sat Arnold Palmer. Bohn got his courage up to ask the King for some advice.

“Mr. Palmer,” Bohn started, “if you were here, would you just punch out or try to execute the shot, or well, what would you do?”

There was a pause, then Palmer broke the silence: “I would never be here,” he quipped.

Point taken. Don’t hit your tee shot into the right trees at 18.

Dicky Pride finished up his college days at Alabama and headed to Orlando to play the Florida mini-tours. A former college teammate sent him an application for a junior executive membership at Bay Hill. He met Arnold Palmer, who helped him get approved, and therein started a beautiful friendship.

In November of 1992 Pride was ready to get started. On the putting green one day, Palmer said to him, “You’re going to turn professional, aren’t you?” Pride told Palmer that yes, that was the plan. So Palmer said, “Can I give you some advice? There are no miracles in this game. You only get out of it what you put into it.”

When the two parted ways that day, Pride hustled into the pro shop and frantically asked for a sheet of paper so that he could write down Palmer’s exact words. “I mean, this isn’t just my idol,” Pride says, “he’s my father’s idol, too.”

Shortly before Palmer passed away in 2016, Pride asked Palmer’s secretary to type up the advice Palmer had given him, with the date included, on Palmer’s own letterhead. He then asked Palmer to sign it. Pride’s original sheet and the typewritten paper both hang in Pride’s office. As he tells the story, Pride wipes away tears.

“That man, and Finsty (Dow Finsterwald, who wintered at Bay Hill), they did so much for me,” Pride said. “I would be up in Arnold’s office all the time, asking him questions. One time he told me, ‘Come see me tomorrow. Let me think about that before I tell you something.’

"You know, Mr. Palmer never gave you the answer; he gave you a way to get to the answer. You had to work.”

Robert Damron had a very special window into the world of Arnold Palmer. The Damron family moved from Kentucky to Florida and settled into a house just off the 10th green at Bay Hill. They joined the club, and Robert’s dad became good friends with Palmer, playing cards and playing alongside him often in the club’s famed daily Shootout.

On his way to earning a PGA TOUR card, Robert also played a lot of rounds with Palmer. Probably 80-100, he estimates. Damron’s rookie season, he did not get into the Bob Hope tournament in Palm Springs on his number. Palmer constantly was asking if there was anything he could do for Damron. Damron usually said, "You've already done enough for me." This time, he wanted to play the Hope, and asked, “Could you make a call?”

The next day, during the Shootout, Damron was playing behind Palmer and his dad. When he got to the third green, there was a business card in the cup. On the back of it read, “RD, you’re in the Hope.” When Damron played nicely in his first round of the tournament, there was a fax (yes, remember those?) already awaiting in the scoring area. It was from Palmer. “Good playin’” is all it said. Says Damron, “He always paid attention.”

From time to time, on mornings he might be hitting balls next to Palmer at Bay Hill, Damron had to remind himself: Arnold Palmer is just one of the guys. Then again, he was anything but just one of the guys.

Damron: “This is one of the most famous, and revered, men on this planet, and one of the most important men that sports – not just golf – has ever created. When (Muhammad) Ali died (in June 2016), I thought, there is one true sports icon left that transcends his own sport, that everyone knows.

"Occasionally, that realization would hit me. But he was just Mr. Palmer. He was just one of us.”

Brad Faxon joined Bay Hill as a young PGA TOUR pro in the mid-80s,, taking advantage of great weather, lots of area TOUR players to find games, and one of the state’s top golf exams at Bay Hill. Faxon always appreciated seeing Arnold Palmer at home, in his element.

Faxon actually got paired with Palmer in Faxon’s first PLAYERS Championship. He learned a lesson that day that has stuck with him since. Palmer hit a shot that got a terrible break, his ball taking a bad kick and coming to rest directly behind a tree. Faxon was curious to see Palmer’s reaction once he got to his golf ball and saw his predicament. Would he show his frustration? Would he curse the golf gods that put his ball in such a spot?

Palmer looked at his ball, looked up at the tree, and said to no one in particular, “I hit it there. I hit it there.” Says Faxon, I use that every time I want to get down on myself.”

Closer to home at Bay Hill, Palmer constantly was tinkering with his equipment. He had a garage filled with clubs, and even kept supplies such as tape and a knife in his bag. He would cut a leather grip, spin it off the club, then re-wrap it to hit another shot.

Palmer still was playing some Senior Tour events back then. What always resonated with Faxon, he said, was seeing how much Palmer loved the game.

Faxon: “I measure people and ask, are they really a golfer, at heart? Do they live and die with the game? Arnold was a golfer. Jack (Nicklaus) might not have been a golfer, he was a competitor. I don’t know that they love the game. Arnold couldn’t wait to get out on the course, and hit shots, and play with his members, and talk about the game.

“I loved that about him. It was beautiful.”