How Ben Hogan put Seminole on the map

12 Min Read

Written by Jim McCabe

TaylorMade Driving Relief trailer

You knew that golf would lead the return of live sports competition of any kind at the highest level in the United States. Given its inherent physical distancing, it was just a matter of when and where for players and fans to reconnect in the era of COVID-19.

TaylorMade Driving Relief on Sunday, May 17, forever will mark the reentry. It's an 18-hole team skins match pitting Rory McIlroy and Dustin Johnson against Rickie Fowler and Matthew Wolff. Four-ball format will be used throughout. All $4 million committed is reserved for relief efforts for the pandemic. There is no prize money for the professionals.

RELATED:Fans at home will be able to contribute to TaylorMade Driving Relief’s COVID-19 relief efforts thanks to PGA TOUR Charities’ online and Text-To-Give donation platforms powered by GoFundMe Charity.Click here to donate.

When that beacon of uncanny mental strength and aura – a man to whom Barry Van Gerbig owed everlasting gratitude for providing his life with purpose – performed one final act at Augusta National with such fortitude, emotions were left uncontrolled. And so, Van Gerbig cried. And cried. And cried.

More than a half-century later, the tears have dried, but the memory lingers of that April Saturday in 1967 when Ben Hogan – age 54 and wearing an impeccable pride as neatly he did his trademark cap – played as splendid a sequence of golf shots as the game has ever seen. There were birdies around Amen Corner, Nos. 11, 12 and 13, a scintillating 30 strokes on the back nine, and with a 6-under 66 that the esteemed Herbert Warren Wind suggested sent patrons home “as exhilarated as schoolboys,” Hogan provided an emotional epilogue to his Augusta National experience.

From where he sat in Juno Beach, Florida, Van Gerbig savored that television moment, knowing, too, it was an epilogue to the Seminole Golf Club experience.

“If not for Ben, no one would have ever heard of Seminole,” Van Gerbig says. “His ghost is still felt.”

Golfers are involved in these words, but this is not a golf story. It’s a love story. Van Gerbig’s love for Hogan and Hogan’s love for Seminole. He first visited there in the 1930s and if at first Hogan stopped in at Seminole as part of the professional winter circuit in Florida, the embrace soon became far more personal. To the point where, while you are correct to forever identify Hogan with Shady Oaks and Colonial and Riviera, you should appreciate that he might have loved Seminole more than anywhere else. And not just the golf course, but the warmth, the ambiance, the camaraderie, the serenity, and the intrigue of the club.

To rekindle this love story seems fitting in advance of Sunday’s TaylorMade Driving Relief competition to be held at Seminole – Rory McIlroy and Dustin Johnson vs. Rickie Fowler and Matthew Wolff in a team skins game – that will be the first taste of professional golf since an insidious pandemic turned our world upside down.

While the Golf Channel broadcast will give a golf-starved fandom its first taste of live competition in two months – albeit a charitable affair for COVID-19 relief – in all due respect to their mighty talents, McIlroy and Johnson and Fowler and Wolff will not be the stars.

It will be Seminole.

To say there is a mystique about Seminole is akin to suggesting there is warmth from the sun. If the legendary Pine Valley blows you away immediately with its aura and immense challenge, and Cypress Point leaves you breathless with its raw beauty and majesty, Seminole begs your patience. It entices you but doesn’t unfold all its glory on that first visit. Instead, the nuances to the golf holes are appreciated the more you see it, the history to the club enriched the more you study it.

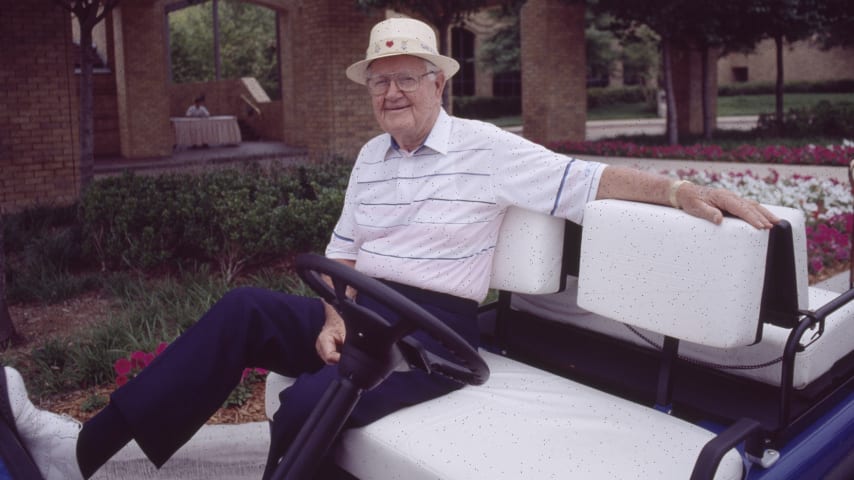

And if you could get 80-year-old Barry Van Gerbig to stop hitting balls for a bit, he’d tell you about Ben Hogan, who is so much a part of that Seminole history.

A Donald Ross spectacular set firm against the Atlantic Ocean, Seminole’s holes are angled in such a way that you rarely play two in a row with the same wind. Hogan loved that about Seminole, said Van Gerbig, a former club president who has walked this course for parts of seven decades. His father, Howell Van Gerbig, was club champion in 1939, and Barry and his older brother Mickey were part of the Seminole scene in the 1960s, which is where his story of getting to know “Mister Hogan” begins.

By then, Hogan was renowned for using Seminole to tune-up for the Masters. But while Van Gerbig doesn’t dispute that Hogan did find Seminole to be a proper prep for Augusta National – what with firm turf and difficult greens – the overriding reason for his annual March trip to the course was pure pleasure. “He loved Seminole, he had good friends here, and he enjoyed the peace and quiet,” Van Gerbig says. “And Seminole loved having him.”

In the ‘60s, the Van Gerbig brothers were in their 20s and as winter fixtures around Seminole, they became entrusted with responsibilities to assist Hogan. (Mickey had played golf at Rollins College and pursued law; Barry had played hockey at Princeton and dabbled on Wall Street and joined a group that bought an NHL expansion team.) They would drive Hogan to and from the club, seeing to it that he had what he needed, join him for golf when requested, leave him alone when required.

Sounds like the perfect job if you’re into golf, as Mickey and Barry were. But decades later, Barry cherishes that Hogan had substantial character that ran deep, that he picked up on things around him and was willing to be a mentor on matters more important than golf. Admittedly comfortable in a privileged lifestyle with which he had been blessed, Van Gerbig in those post-Princeton years wasn’t applying himself to his potential and Hogan knew it.

“He changed my whole life around,” Van Gerbig says. “He stopped me one day, looked me in the eye and said, ‘Son, I’ve got to tell you something. You need to find something else (in life). You haven’t earned this life.’ ”

There was not a shallow bone in Hogan’s body, adds Van Gerbig, who was inspired by his mentor to return to college for a master’s degree in medical psychology.

“He had worked for everything in life,” he says. “I saw his way of approaching golf, his commitment to hard work. It was a tremendous education.”

The Hogan routine was a study in excellence, notes Van Gerbig. There was a thought process to everything the man did and studying the nuances of Seminole was Hogan’s passion. “Playing the angles,” recalls Van Gerbig, explaining the Hogan mantra. “He once told my brother (Mickey) and I, ‘Listen, if you want to learn from me, don’t watch my golf swing; that will ruin you. But watch the way I play the golf course.’ ”

Mind you, by the time the ‘60s rolled around, Hogan playing Seminole was like Sinatra singing Cole Porter. He had first visited the place in 1937 as an aspiring professional working his way along the Florida winter circuit, accepting an invitation into the debut of what was then called the “Seminole Amateur-Professional.” With a 141 for two rounds, Hogan shared third with another youngster born in 1912, Sam Snead.

In recent years, there is a new generation of golf writers who have pounded social media with tweets and blogs and Snapchats about the Seminole Pro-Am as if it is a new-found phenomenon. The wheel, alas, is constantly re-invented.

The fact is, this March gathering was considered an “unofficial” staple to the PGA TOUR from 1937 through 1961 when it was disbanded, only to be revived in 2004. Yes, it is a “must play,” and elite players love the break from the mundane. But the foundation of character and personality had been poured generations ago, back to a day when the members were Joseph Kennedy and Henry Ford, Paul Mellon and the honorary Dwight Eisenhower. Oh, how they loved these sandy links that owed its beginning to E.F. Hutton’s astute purchase back in 1929 and the wise choice of Donald Ross as designer.

But beyond a winter escape for the wealthy, Seminole was a superb test for professionals touring Florida in the winter. Hogan teed it up for a second time in the Seminole Pro-Am, in 1940, and pretty much was there every March from there on, save for the years of World War II, and those when he was hurt.

His closest friends became men of great business acumen – George Coleman and Paul Shields – and for sheer entertainment there was the mysterious and larger-than-life Chris Dunphy, who was likely to be talking to his great friend Bing Crosby about their recent match against the Duke of Windsor or promoting Joe Kennedy’s son Jack as a potential presidential candidate.

Seminole men, all of them, and it was into this setting that Hogan felt exceedingly comfortable as his career took off in the 1940s, morphed into icon status in the 1950s, and gracefully transitioned into retirement mode in the 1960s and ‘70s. His great friends Claude Harmon, a fellow Texan, and Henry Picard, who corrected Hogan’s nasty hook, were longtime head professionals at Seminole and everything about the place was saturated in a style and ambiance that Hogan loved.

From the fact that the wealthy membership tended to sleep in after “high society” evenings so Hogan had the place to himself for hours of morning practice, to the varying winds that enabled him to polish his uncanny shot-making, to a clientele that admired his accomplishments but extended him great respect to his desire for privacy, “Hogan felt at home at Seminole,” says Van Gerbig.

The annual Seminole Pro-Am was a big part of the joy. Hogan and his fellow pros were the reason the public was given the chance to buy tickets. Some years, the crowd was kept to 1,000, other times, like in 1960 when Crosby teed it up, 5,000 people showed up.

To that crowd’s delight, Crosby came through, teaming with Gardner Dickinson for the win. But big-name winners were not an anomaly at the Seminole Pro-Am and the rollcall of winning teams includes a parade of stars. Sam Snead, Byron Nelson, Jimmy Demaret, Lloyd Mangrum, Peter Thomson, Julius Boros, Cary Middlecoff, and Arnold Palmer were winners “back in the day,” and today’s era has produced as proficiently – Ernie Els, Davis Love III, Justin Rose, Rickie Fowler, and Rory McIlroy have all triumphed.

Hogan is included. He teamed with polo star Michael Phipps in 1947, their best-ball 63 winning what was then billed as the “Reed Latham Amateur-Professional tournament.” Hogan, then 34, naturally anchored the team effort, though he gave credit where credit was due during the presentation ceremony – to Phipps, whose lengthy birdie putts at the 16th (30 feet) and 17th (20 feet) provided the winning plays.

It was a productive windfall for Hogan, who earned $1,500 for the team victory, $475 for his share of fourth in the pro division, and a whopping $1,700 in “the action pool,” which was nonchalantly reported in the newspapers.

When Hogan arrived in 1961 for his annual March trip to Seminole, he was 48 years old and a Palm Beach Post story welcomed his arrival by reporting that he was at a point in his career where his only tournaments were “the Seminole,” Masters, Colonial, and the U.S. Open. In fact, he especially looked forward to that year’s Seminole Pro-Am for a good reason.

“Nelson, Hogan, And Snead to Compete at Seminole,” blared a Palm Beach Post headline on March 12, 1961.

Two weeks later, the tournament attracted an enthusiastic crowd, most of them there to watch “The Great Triumvirate.” Snead posted 143, Hogan 146, Nelson 147 as a young gun named by Palmer won low pro honors at 138. Indeed, the baton had been passed; Hogan knew it as well as anyone, but he also recognized that his time at Seminole would remain precious to him, even if the rich flavor of the pro-am would no longer be part of the trip. (It was not held between 1962-2003.)

He had shot scores of 63 and 65 at Seminole that spring and for the next few years he remained diligent in his preparation to the Masters. These were the days when the Van Gerbig brothers were there for Hogan, be it to drive him around, join his foursome, stoke the grill for dinner, or simply to talk.

Hogan was north of 50 years old, but the passion was still there.

“No one knew the game any better than Hogan,” says Van Gerbig. “It was so impressive to watch him dissect a golf course. We’d listen to his comments; it had never dawned on us the mental part of the game. He was so focused.”

From 1939 to 1956, Hogan’s time at Seminole paid off handsomely at Augusta – he was top 10 in each of his 14 Masters, including wins in 1951 and 1953. Father Time, of course, caught up, so Hogan in the 1960s was not the Augusta force that Palmer or Jack Nicklaus or Gary Player were. No matter, he was even more of an inspiration to Van Gerbig, who will never forget those March days in 1967 when Hogan would practice in the morning, then play in the afternoon.

“He needed help taking off his shoes,” says Van Gerbig. “He was in constant pain, but his mental toughness was unequaled.”

Imagine, then, how the electricity ran from Augusta National to Seminole that third round, when Hogan turned back the clock and made everyone think it was 1953 all over again. Tied for 23rd and seven off the lead through 36 holes, Hogan captured the sporting world’s fancy with his epic third round. Van Gerbig still gets goosebumps, remembering the joy he felt while watching the action from Seminole.

It matters not at all that Hogan closed with a 77 in 1967 and fell into a share of 10th. It doesn’t even matter that it was Hogan’s final Masters. (He continued to return for annual March trips to Seminole through 1977.) What Van Gerbig will never forget is how TV captured Hogan’s walk to the 18th green to finish off his third-round 66.

“Applause, just respectful clapping, no hollering,” he recalls. “Just applause.”

It sounded beautiful to Van Gerbig. Good thing, too, because he couldn’t see it. “I was crying like a baby.”