Grayson Murray Foundation built on principles of awareness, kindness and support

11 Min Read

Remembering Grayson Murray

Written by Helen Ross

The five of them were sitting in the lobby of a hotel that painful Saturday evening, bonded by their shared grief and unwavering love for Grayson Murray.

A few hours earlier, Eric and Terry Murray had gotten a grim phone call from the Palm Beach Gardens police department. Their son Grayson, a PGA TOUR veteran who experienced anxiety, alcoholism and depression, had taken his own life on May 25, 2024. He was 30 years old.

A family friend, Jeff Maness, arranged for a private plane to take him, the Murrays, Grayson’s golf instructor and long-time mentor Ted Kiegiel and Kiegiel's wife to South Florida. The five were still trying to process the devastating news when Eric spoke up.

“We’ve got to do a foundation in Grayson’s name,” Eric remembers telling the group during a recent interview in his home in Garner, North Carolina. “And it’s got to be big. It can’t just be a junior golf tournament. It’s got to be big. We need to do something that we can help a lot of people.

“This is a broad subject – mental illness or depression. I bet if you knock on every single door in this neighborhood, there’s somebody either in that house or they know someone who goes through depression. So, it’s a real need.”

Grayson, who won his second TOUR event a year ago this week at the Sony Open in Hawaii, once told his dad that he wanted to help others who were also experiencing mental illness and addiction. Eric had even bought domain names for a potential website after his son was treated at the Hazelden Betty Ford Center. But cruel reality altered that dream.

In the months after Grayson’s death, though, as his parents were going through his things, they came across several pages of a notebook, the first dated July 24, 2021, which was while he was in the treatment facility. He wanted to host a golf tournament to raise money for people who needed treatment but whose insurance would no longer fund it. He wrote about holding an auction and reaching out to potential donors. He even mapped out a series of links for a website for the Grayson Murray Foundation.

And the mission statement? There, in Grayson’s own handwriting, are the words: "Help the ones that want to be helped but might not have the help they need financially."

The Murrays had their mandate.

“I thought, 'Oh wow, this is the path the foundation needs to go,'” says Terry, Grayson’s mother. “I said, 'We've got our starting point.'”

“That's what he wanted to do,” Eric agrees. “And he would've done it if he'd have gotten himself back. And I think he was real close. I really do. I think he was real close, but he went down that last hole.”

The Grayson Murray Foundation, which aims to foster awareness and support research and continuing access to mental health services, officially launched in Honolulu this week. Grayson was remembered Tuesday in a traditional Hawaiian celebration of life on the beach by the 16th hole at Waialae Country Club. Fellow TOUR players and caddies will keep his message alive by wearing “GM” buttons during the Sony Open, which he won last year with a magical 39-foot birdie putt on the first playoff hole.

From left, President of Friends of Hawaii Charities Corbett Kalama, Eric Murray, Terry Murray, Cameron Murray, and Erica Robinson participate in a Celebration of Life service honoring Grayson Murray before the 2025 Sony Open in Hawaii at Waialae Country Club in Honolulu, Hawaii. (Maddie Meyer/Getty Images)

The week undoubtedly will be bittersweet for the Murrays and the rest of the GMF board of directors who made the 4,700-mile trek to Honolulu from the East Coast. There will be some work, some brainstorming on future projects and alliances, to be sure.

“But we also hope it's the time to just think about Grayson from the year before when he was there and so happy,” Terry says.

Members of the PGA TOUR community attend a Celebration of Life service honoring Grayson Murray prior to the 2025 Sony Open in Hawaii at Waialae Country Club in Honolulu, Hawaii. (Maddie Meyer/Getty Images)

“We were fortunate,” Grayson’s sister Erica agrees. “The last year of his life was probably the best year of his life.”

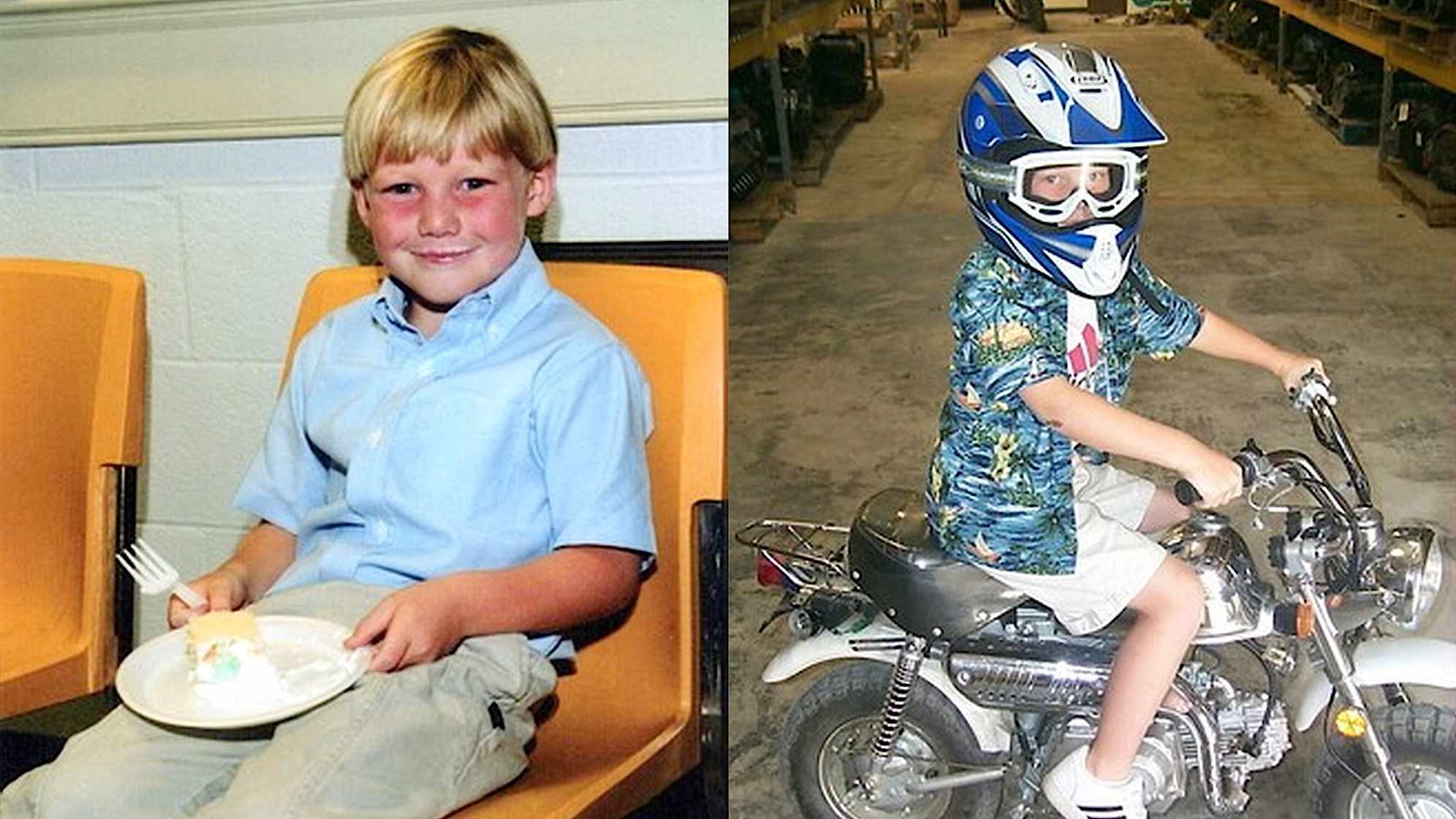

A gifted athlete like his brother and sister, Grayson took to golf immediately. When he was 8 years old, he tagged along to the driving range with his father and older brother Cameron. Although he had never played before, Grayson quietly began launching balls into the air. The club pro was so impressed he offered to give the youngster lessons for free.

Grayson soon began working with Kiegiel, who Eric says was like a “second dad” to his son. He became one of the top amateurs in the country, winning three straight IMG Junior World titles.

He was just 19 in 2013 when he played in his first U.S. Open. He earned the prestigious Arnold Palmer Scholarship at Wake Forest but stayed for just one semester. He also had abbreviated stints at East Carolina and Arizona State.

The game Grayson loved also brought out the perfectionist in him and magnified what was later diagnosed in his teens as social anxiety. The feeling was so acute at the 2014 Southern Amateur that he walked off the golf course when he was in contention. Eric remembers another time when Grayson essentially lost his swing coming down the stretch.

“I actually saw his medical records, and I saw where Grayson had told the psychiatrist that he liked to be in the top 10, but he didn't like to win anymore,” Eric says. “And this had been going on for some time. He didn't like the attention. And that was part of the social anxiety.”

Exacerbating the situation, his parents say Grayson began experimenting with alcohol when he was in high school. As he started traveling and playing professionally, beer and cocktails helped fill the solitary nights on the road. He began gambling, too. Terry recalls driving to The Greenbrier in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, to join her son at a TOUR event. One of the attractions at the resort was a casino.

“We had dinner that night,” she says. “And then he got on the first tee and pulled out. I didn't know what he had done before I got there, because while I was there, it was perfect. But he had evidently lost in the casino big the night before and then couldn't get it out of his mind. So, we drove all the way back home.”

Over the last 18 months or so, though, Grayson, a two-time TOUR winner with three Korn Ferry Tour wins as well, had gotten sober and became comfortable sharing his story. He even talked to the head coach of one of his favorite sports teams, the Carolina Hurricanes, and offered to talk to their rookies about the challenges of life as a professional athlete.

At The RSM Classic in 2023, Grayson told reporters he hadn’t had a drink since he went on a bender at the Mexico Open at Vidanta that morphed into a frightening four-day anxiety attack.

“I did not want to go through that ever again,” he said at the time, “and that was the last time I had a drink.”

Only, it turned out that it wasn’t.

“At the tail end, at the very tail end, the very day that all this happened, he started drinking,” Eric says.

Grayson withdrew after playing 16 holes in the second round of the Charles Schwab Challenge, citing illness. He flew to Palm Beach Gardens, where he had a home. Both Erica and Terry remember sending texts to him that went unanswered.

“I could tell he was down,” Erica says. “So, I had sent him a video of (my son) Dylan saying, ‘I love you, Grayson.’ And he never responded. So, I thought something is not right because he would always respond or at least give it a heart or a thumbs up.”

Grayson was so much more than the headlines. His suicide. The scooter accident in Bermuda. The photograph in shorts and a t-shirt and a missing tooth when he got his TOUR card. Other outbursts along the way.

“Even I struggled with that,” Erica says. “ I mean, he was my brother, and there were days where I just wanted to be like: Why, Grayson? Why are you acting like that? But I didn't understand that there was something deeper going on. And so, once I learned that, it all made sense.

“But that's not something a lot of people necessarily talk about to the outside world. And I think we need to show people exactly what Grayson said, (that) it's okay to not be okay, and it's okay to ask for help.”

Erica, the middle of three siblings who is four years older than Grayson, serves as secretary of the foundation. She and her mom, the organization’s treasurer, both have taken college classes on starting non-profits. For them, Eric and older brother Cameron, the foundation is a labor of love.

Erica remembers Grayson as a prankster, as well a “really, really great uncle” to her two sons. She talks about the time he got Tiger Woods to join a FaceTime call with her oldest and wishes she had taken a screenshot of the conversation. She says he became a completely different person after he became sober and embraced his faith.

Grayson’s dad recalls his kindness to a youngster who was in tears after being berated by another child’s father during a junior tournament. Grayson, who was playing in the same group, took the boy’s golf bag and carried it along with his for the rest of the tournament. The two kids became fast friends.

Grayson loved animals, and once gave his caddie money to buy food for some stray dogs they’d seen on an island. He even asked his mother to see if she could find a way to bring them home to the U.S. When he was at his folks’ home in Raleigh, he’d sit on their back deck for hours playing fetch with their dog Toby.

When news of Grayson’s death became public, the Murrays were overwhelmed by the outpouring of emotion. Erica’s soccer teammates remembered him as their little “mascot.” A middle school girlfriend sent flowers. High school teachers wrote notes. President-elect Donald Trump and First Gentleman Doug Emhoff reached out, too.

Maybe it shouldn’t have surprised the Murrays, though.

“Even when he was in his darkest moments, he would reach out to other people who had the same need that he had and try to console them,” Eric says.

“People that were with him at Betty Ford would say how many times Grayson would reach out to them,” Terry recalls. “And even (PGA TOUR Commissioner) Jay Monahan, we didn't know that Grayson was the first person that when Jay turned his phone back on after being away, that Grayson was the first text he had.”

In the months since Grayson’s death, the family has focused on the foundation and finding ways to help others deal with the kind of challenges that plagued him. Funding to continue care when insurance has run out is of prime importance. But the Murrays would also like to partner with programs to prevent bullying in middle school and perhaps help children with a parent who died by suicide. Therapy dogs would speak to Grayson’s love of animals, too.

They look to him – and his notes – for guidance.

“They always say that when someone dies, they send you signs,” Terry says. “And cardinals are one of the things that people see. With us, it has been butterflies.”

Flocks and flocks of the insects with brightly colored wings frequented the Murrays’ garden last summer. Terry even noticed one on the wall of the emergency room she went to recently after she tangled with the door of the dishwasher.

There are other reminders, too. Terry unknowingly giving Dylan the same truck for Christmas that Grayson had given him as a gift the previous year. Cameron talking with friends about his brother in a Florida sports bar only to see a video of Grayson on the TV.

The Grayson Murray Foundation will help them all move through their grief.

“It used to be to mental health was sort of brushed under the rug,” Terry says. “We never talked about it. It's like Grayson was so open about the fact that, 'Yes, I suffer from anxiety and depression,' and he spoke about it.

“Some of the cards that we received, people would say things like, 'I suffer with some of the same things that you do, and now I feel like I can talk about it, and I can get the help I need or something. … So, you've given me the confidence to be able to go and do something about it.'”

Grayson would surely be proud.

To help support the Grayson Murray Foundation or learn more, please visit graysonmurrayfoundation.com or contact Foundation President Jeff Maness at jeff@graysonmurrayfoundation.com.

If you are experiencing a mental health crisis, please call the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the United States at 988 or visit their website at 988lifeline.org.