Lasting legacy: The untold bravery of the Greensboro Six inspires golf's next generation

7 Min Read

Written by Helen Ross

GREENSBORO, N.C. – Long before he became a golf personality and influencer, longer still before he appeared on the “Big Break,” Will Lowery used to spend every Christmas holiday at his grandparent’s home, just two blocks from Gillespie Golf Course.

More than once, his grandparents told Lowery about the Wednesday afternoon in December 1955 when Dr. George Simkins Jr., a local dentist, and five of his friends attempted to integrate that municipal course so close to their house. It was six days after Rosa Parks famously declined to give up her seat on that bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

The 37-year-old Lowery was impressed by the courage of the men, who were arrested and came to be known as the “Greensboro Six” as they took their fight all the way to the Supreme Court.

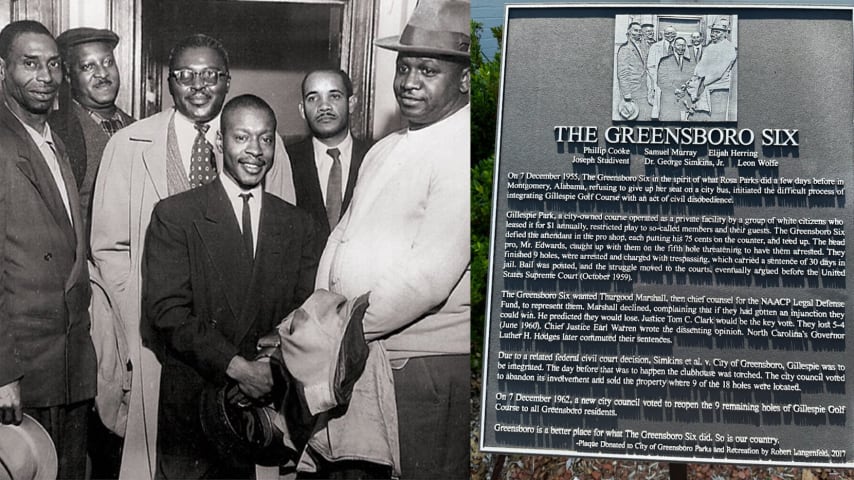

This photo of the Greensboro Six is engraved on a plaque in front of the clubhouse at Gillespie Golf Course. (High Point University Archives)

“I always like to think that I lead by example,” Lowery said. “I'm always willing to sacrifice. And the fact that there were six guys that were in alignment in their thinking. They had diversity of thought to come out here and just say, ‘Hey, we don't care what happens. We believe that it's some injustice that is happening,’ and they were willing to face any consequences.

“Just kind of understanding the pushback and resistance that they had to face is important. And that just kind of paints a picture of how it was back then. We're so blessed from some of the things that those guys encountered and endured that we can have the ability to come to walk on Gillespie golf course.”

On Monday, the engaging Black man with the long dreadlocks was at Gillespie hosting a clinic for the kids at First Tee-Central Carolina. Four-time PGA TOUR champion Charley Hoffman was on hand to show the youngsters his arsenal of golf shots and Wyndham Championship officials announced a $200,000 donation to the local First Tee chapter.

And a year from now, the clinic will have a decidedly different look when a mural commissioned by Wyndham Rewards celebrating the Greensboro Six is complete. It will be painted on the large outside wall of the First Tee building overlooking the practice area.

The outside wall of the First Tee building, where a mural commissioned by Wyndham Rewards will be painted. (Zachary Stinson/Travel + Leisure)

The way Lisa Checchio, chief marketing officer of Wyndham Hotels & Resorts, sees things, the symmetry between the First Tee and the accomplishments of the Greensboro Six couldn’t be more striking.

“They get the opportunity to play on a course with such historical significance, but they are part of the history of this course as they grow forward, right?” Checchio said. “Them being here, being able to play, have their headquarters here, learn to love a sport that can be a lifelong sport. They're creating their own history here.

“So, if they recognize it today or when they look back on it in the future this is a special place, and I think these kids will know that.”

Lowery senses that significance as well. On Monday, fully aware of the history of the course his grandparents first told him about, he felt things come full circle.

Gillespie was one of two municipal golf courses in Greensboro in the 1950s. But Nocho Park Golf Course, which was for Black golfers, had fallen into disrepair. The men who leased Gillespie essentially made it a private course for Caucasians only, although white players could play regardless of whether they were members.

A plaque commemorating the Greensboro Six at Gillespie Golf Course. (PGA TOUR)

So Simkins, who became one of Greensboro’s preeminent civil rights figures, and his friends – Phillip Cooke, Joseph Sturdivent, Samuel Murray, Elijah Herring and Leon Wolfe – decided to try and make that change. They paid their greens fees, which came to 75 cents each, and teed off. Soon the head pro, Ernie Edwards, confronted them on the course.

“He was following us around, cursing us and threatening us, and I told him ‘We're out here for a cause,’” Simkins remembered in a 1990 interview with the Greensboro News & Record.

“And he said, ‘What kind of a cause?’ and I said, ‘The cause of democracy.’”

Simkins was so unnerved by the situation that afternoon that he recalled keeping a golf club in his hand for protection. After nine holes, the six Black men decided to stop playing, but their troubles were just beginning.

“That night they had the Black officers come around to my house,” Simkins said. “They arrested us and took us down and booked us. During the trial, the sheriff, the solicitor and the judge, they were all grouped together, laughing, lying on the stand, and I just couldn’t understand – of course I was naïve – why you couldn’t get fair trial.

“It was all made up that they were going to find us guilty.”

The sentence was 30 days in jail. Simkins once said he would remember the judge saying, “Take them away, sheriff,” for the rest of his life. His father, who was also a dentist, ended up paying the bond for all six.

The Greensboro Six, who have all been dead for two decades now, appealed to a federal court where Johnson Jay Hayes of North Wilkesboro was the presiding judge. Hayes issued a declaratory judgement that anyone who paid taxes and could be called to fight for the United States had the right to use public recreational facilities. He ordered the club to be integrated within three weeks. Two weeks later, the clubhouse burned down in a suspected arson, and the course was condemned.

The trespassing conviction was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1959. But the lawyers left the declaratory judgement out of the record, and the Greensboro Six lost in a 5-4 decision. Following the ruling, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote a strong dissenting opinion that swayed Luther Hodges, then-governor of North Carolina, and he commuted their sentences.

For Simkins, the entire episode turned out to be a life-changing moment.

“The way they were treating me in the courts, I said, ‘I’m going to devote my life to civil rights,’” said Simkins, who became the long-time leader of the local NAACP chapter as well as a prominent national figure. He is immortalized by a statue on the grounds of the old Guilford County Courthouse.

Gillespie was refurbished and became a frequent site of tournaments on the United Golf Association tour, attracting prominent Black golfers like Charlotte native and World Golf Hall-of-Famer Charlie Sifford and three-time PGA TOUR winner Jim Thorpe of Roxboro, North Carolina. Sifford also was the first Black man to play in a PGA TOUR event in the South at the 1961 Greater Greensboro Open (now the Wyndham Championship) at Sedgefield Country Club, where he endured death threats.

Richard Watkins, the first-ever men’s and women’s varsity golf coach at North Carolina A&T State University, met Simkins in 1975. Watkins, who recently retired, remembers his long-time friend and golf partner as a humble man who rarely talked about what happened that December day.

“He knew the significance of what of what he did,” Watkins says. “But to get it out of him, you had to ask him, and you had to ask the right questions.”

Gillespie is 2 miles from A&T, a thriving HBCU with just over 13,000 students that was founded in 1981. Five years after Simkins and his friends attempted to integrate the golf course, four students from A&T went to the segregated lunch counter at the F. W. Woolworth store in downtown Greensboro, sat down and asked for a cup of coffee and a donut.

The four freshmen were refused service but remained seated at the lunch counter until the store closed. The sit-ins continued – eventually reaching nearly 1,000 strong – until July 25, 1960, when four Black employees were finally served a meal there. The protests were the most renown of the civil rights movement.

Watkins likened the mural to the bronze statue of the Greensboro Four on the A&T campus and to the lunch counter in the Woolworth building featured in the International Civil Rights Center & Museum downtown. He says the painting on the stark white wall outside the First Tee building will spark conversation and serve as a daily reminder of the struggles Blacks face as they strived for equality.

“A lot of people come out (to) this golf course, they'll come out and hit balls, see that mural, and they won't have not one inkling of the significance, the historical, the racial significance of what happened,” Watkins said. “But they'll see that mural and they'll ask, and when they ask, somebody like me will be standing around that won't mind sharing that information with them.

“So, I think that's probably, in my mind, that's a tremendous idea for that mural on that wall. You're going to see it, all you got to do is come up here. It's great.”

Two decades have passed since the last member of Greensboro Six died, yet their story remains a powerful one.